Advertising

TLDR: Unchecked advertising is a drain on attention and can result in Molochian rat-race dynamics while ruining the commons. Utopia limits advertising to specific spaces and budgets.

Prerequisites: Licensure

One of the recurring themes of these essays is that free trade is good. Only in the case of negative externalities or poor judgement should we be wary of people making deals that make both parties better off. In some sense this is a very pro-capitalism perspective, but there’s an aspect of capitalist culture as we know it today that I am strongly against: advertising.

A big part of my opposition is that advertising is not trade. There are no deals being made between marketers and the consumers of their ads. In many cases advertising leaves both parties better off, and we’ll dive into those cases in a moment, but in most cases the people who see ads are victims, made worse off by the actions of the advertiser without their consent.

The largest and most prominent way in which advertising hurts people is that it takes one of the most precious things we have: attention. Distractions can, in theory, be good. We need to shift attention to important things as they come up. If a tiger is lurking in the bushes, it’s important for me, for my own safety, to be distracted by that flash of color and movement. But in a world where color and movement are easy to create and use against us, the average person is being regularly robbed of the ability to think, especially in long, sustained periods.

This kind of theft is so ubiquitous and each distraction so minor that we rarely step back and notice, particularly in cities, just how toxic the environment is for focusing. Each individual ad is part of a death-by-a-thousand-cuts and, with a few exceptions, rarely seems worthy of any response stronger than a moment of annoyance.

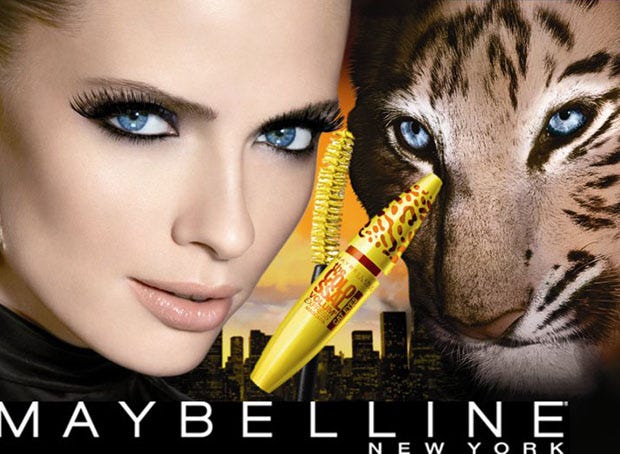

But it’s worse than this. Advertising doesn’t just distract — it distracts with manipulative, parasitic, messages that erode our ability to make sense of the world. Are you a Pepsi drinker or a racist? Do you think a necklace or earrings are how you’ll show your wife that you love her on valentine’s day? Are you one of the cool kids who gets to eat chocolate blasted sugar bombs that are part of a balanced breakfast? Are you a manly man — the kind that drives a truck? Are you a beautiful woman — the kind that looks like a photoshopped tiger?

It’s easy to feel immune to these kinds of things. They’re easy to see-through when confronted explicitly, and I’m unsure how much they effect thoughtful people who put forward an effort to see through them. But not everyone is thoughtful, and at the very least they produce a kind of semantic noise that makes the theft of attention even worse.

And let’s not forget that in many cases advertising is simply ugly, especially when it’s in a public space filled with other ads competing to be the most high-contrast thing in sight. Some advertising is beautiful, some is charming, some is funny, but most is just noisy garbage.

A Race to the Bottom

While advertising may be annoying, ugly, distracting, and manipulative to the average person, perhaps the combination of helpfulness to the minority and benefit to companies is worth it. In a world without advertising fewer win-win trades might occur due to consumers not knowing about beneficial or superior products, and we might be poorer as a society.

I think this is a non-crazy hypothesis to consider, and we’ll revisit it when thinking about superior alternatives to traditional advertising. But I want to point out that advertising can also be bad for corporations and consumers, not just the public.

Consider two rival corporations, e.g. Pepsi and Coca-Cola. In the good old days neither one spent much on ads. Then, one day, Pepsi hires a new head of marketing who suggests spending a lot more on advertising to see if it boosts sales. The company leadership agrees to the experiment, and behold: sales go up significantly. People are thinking more and more about Pepsi, and less and less about Coke. At the next board meeting the Coke leadership looks at their quarterly profits and explains that Pepsi has been capturing more market-share thanks to advertising. In order to stay relevant, Coke boosts its ad-spending and behold: sales figures go back up. It may even be the case that afterwards, both companies are selling more soda than they were before the advertising boost, as they take market share away from other drinks.

But consider: what if this happens again? Perhaps Coke spends even more on advertising, and successfully steals market-share from Pepsi, only for Pepsi to match that spending and bring it more into parity. We can repeat this as many times as we want as long as spending even more on ads results in a corresponding short-term change in market-share capture.

One way of modeling this is as a dollar-auction. Each company burns money in competition over a fixed (or mostly fixed) consumer-base. In the end, both companies might be spending billions of dollars in advertising only for it to be similar to the old days: some people drink Pepsi and some drink Coke. If those companies could collaborate, those billions of dollars could’ve been spent making the world a better place, but because of the competitive race-to-the-bottom, that money is essentially wasted. Neither company can unilaterally spend less on advertising, either, as to do so would result in the opponent stealing their market-share and driving them to bankruptcy.

It’s worse than this, too. In a world where large corporations spend billions of dollars in rent-seeking ad wars, smaller brands (including those with superior products!) can’t afford to advertise their alternatives. This hyper-competition of big-business produces a landscape that is oligopolistic — discouraging competition and innovation from small-business and startups.

The Good of Ads

One of my favorite pieces of writing on the topic of advertising comes from Kevin Simler’s excellent blog, Melting Asphalt:

I know it’s popular these days to underscore just how biased and irrational we are, as human creatures — and, to be fair, our minds are full of quirks. But in this case, the inception theory of advertising does the human mind a disservice. It portrays us as far less rational than we actually are. We may not conform to a model of perfect economic behavior, but neither are we puppets at the mercy of every Tom, Dick, and Harry with a billboard. We aren’t that easily manipulated.

I know people who have worked in advertising who would disagree, but he makes good points as he goes on to describe some of the important properties of how advertising helps communicate true things such as the existence of tools to solve uncommon problems, the effectiveness of certain products over others, and the trustworthiness of some businesses, either to provide a certain kind of product or to simply not disappear in a puff of bankruptcy. But the real meat of the essay is when he dives into the more subtle, and primary way that advertising generates value: through what he calls cultural imprinting.

Cultural imprinting is the mechanism whereby an ad, rather than trying to change our minds individually, instead changes the landscape of cultural meanings — which in turn changes how we are perceived by others when we use a product. Whether you drink Corona or Heineken or Budweiser "says" something about you. But you aren't in control of that message; it just sits there, out in the world, having been imprinted on the broader culture by an ad campaign. It's then up to you to decide whether you want to align yourself with it.

So for an ad to work by cultural imprinting, it's not enough for it to be seen by a single person, or even by many people individually. It has to be broadcast publicly, in front of a large audience. I have to see the ad, but I also have to know (or suspect) that most of my friends have seen the ad too. Thus we will expect to find imprinting ads on billboards, bus stops, subways, stadiums, and any other public location, and also in popular magazines and TV shows — in other words, in broadcast media. But we would not expect to find cultural-imprinting ads on flyers, door tags, or direct mail.

In other words, advertising mostly works not by tricking people into feeling things, but into presenting an opportunity for self-expression. Owning an iPhone isn’t just about the user interface or hardware or price, it’s about what owning an iPhone says about you to those you care about. And notably, in order for you to trust that wearing Nike sneakers is good at signaling that you’re ambitious, you need to believe that those around you have formed that association beforehand. Advertising sews seeds of symbology that can then be reaped by consumers that buy those products.

I’m not perfectly convinced by this theory. For example, I think I’d expect on priors for makeup and medications to be the sorts of things that wouldn’t have significant advertising budgets, and yet they’re huge (at least in the USA where advertising medication is legal). Perhaps one could argue that we’re self-signaling when we buy things like soap, but I feel that it’s likely that this is merely one piece of the puzzle, and doesn’t explain things perfectly.

Insofar as the cultural imprinting theory is true, perhaps advertising is doing an important service. Like a pantheon of gods, we can select products to show the world who we want to be. Yes, this presses on culture in weird ways and steals attention from the hapless bystanders, but maybe it’s worth it for the opportunity of self-expression?

I don’t buy it.

Utopian Advertising

While advertising seems to be doing some good things for society, I think it’s largely harmful, and only permitted because individual people, corporations, and politicians have little ability to fight it — only collective action can hold back the forces that press us towards an advertising-filled world.

I think Utopia is strong enough, and skilled enough at coordinating, to outlaw advertising except in specific circumstances. Advertising is a local concern, so like things such as speed limits or congestion pricing it’s not regulated at the scale of the world government. Instead, there are local laws governing advertising that vary from place to place. In the most libertarian parts of Utopia it’s unregulated, while in stricter places it’s totally banned.

Most of Utopia, however, has converged on a simple principle. Seeing ads can be harmful to people, particularly because of the way they prey on subconscious associations (whether directly emotional or cultural imprinting) and the naïveté of consumers that can’t spot manipulation and lies. For instance, advertising aimed at children probably steers them away from wisdom and (in an unregulated environment) towards things like addictive substances. In Utopia, as a result, to view ads one must have a license.

The flip-side of this is that it’s illegal to show someone an advertisement without first confirming that they have such a license. As a result, there are no advertisements in broadcast media or public spaces. Children in Utopia grow up having never seen ads, and only sometimes end up seeing ads as adults when they opt-in.

Why would one choose to see ads? Well, some websites or services offer discounts to members that turn on advertising, but the primary value of ads is as information. Ads communicate products and services that might be of interest. Because advertising involves voluntary buy-in, most services with ads work to personalize them to the interests and hobbies of the consumer according to whatever identifying information the visitor has provided.

But mostly, when someone wants information on what to buy they either consult a catalogue or a review service like Consumer Reports or The Wirecutter. Company-provided catalogues and third-party reviews are both typically not considered advertisements in Utopia. Catalogues are only advertisements when they’re unsolicited, and reviews are only advertisements if the reviewer has financial interest in distorting their report. In addition to these pathways there are interviews, guest-lectures, conferences, trade-shows, and storefront signs, all set up to provide clear value to consumers and not harm bystanders.

Companies still have marketing departments in Utopia, but what would have been an advertising budget typically gets redirected towards creating superior products, or at least things like sales or limited-time events that might generate grass-roots hype. Companies donate more money to charities in Utopia, as having a company name/logo on a sponsor-gratitude wall in a museum or whatever is typically not considered advertising.

Brands in utopia are weaker, as there isn’t as much common-knowledge about what a brand “means.” But consumers still routinely adopt new products and superior alternatives thanks to increased emphasis on impartial reviews and word-of-mouth.

People in Utopia, unable to express themselves quite as much through mass-market brands, are forced to resort to art and creative expression. And, occasionally, on symbolism that comes from something besides a business.