Basic Income (Part 1: Welfare)

TLDR: Social welfare programs are theoretically justified as a combination of credit and insurance, and empirically justified in reducing poverty and inequality without reducing overall wealth.

Prerequisites: None

Foundational to: Part 2

“No penalty on earth will stop people from stealing, if it's their only way of getting food ... Instead of inflicting these horrible punishments, it would be far more to the point to provide everyone with some means of livelihood, so that nobody's under the frightful necessity of becoming, first a thief, and then a corpse.”

— Thomas More, Utopia (1516)

In these essays I have at many times when describing Utopia referenced “basic income” (often called “universal basic income” or UBI). By this I simply mean a regular cash payment, much like a paycheck, made by the government to each person, regardless of employment, age, health, or socio-economic status (i.e. not “means-tested”). Implicit here is that this income is significant, and that it might even be possible to live off of only this income, if desired.

Basic income is extremely controversial, both because conservatives tend to object to welfare states and because progressives tend to object to taking care of people by just giving them money (children, homeless, and billionaires alike). Since Utopia also treats some non-human animals as people (with rights, including the right to collect basic income), I’m sure I’m handing even more ammunition to the skeptics.

But I think basic income has a lot going for it, and I think it’s worth exploring both the philosophical principles that make it appealing, and the evidence for whether a universal, livable, basic income might be possible without radically increasing the total wealth/production of society. In Part 1 I’ll be considering whether welfare makes sense in itself, moving on to basic income in particular in Part 2, and Utopia’s handling of it in Part 3.

Let’s begin.

Welfare in Principle

6% of the population of the USA are lazy, no-good moochers who haven’t worked a day in their lives and often sit around complaining, asking for handouts, or even just taking naps. They pay no taxes, and undoubtably cost our economy hundreds of billions of dollars a year.

I speak, of course, about babies, toddlers, and other young children of pre-school age. How great would it be if these people got jobs and started to actually pull their weight for once!

Except, they don’t have the skills and expertise needed to be very competitive in the labor market… Hmmm… Perhaps the best strategy would actually be for them to take out bank loans to pay for their present needs while they focus on skill development, then pay back those loans in adulthood once they start earning serious salaries.

On a totally unrelated topic… Ugh! Old people! They just sit around all day knitting, going to the doctor, and taking naps (these are things old people do, right?). Old people should get a job, too, or at least make good investments earlier in life so that they’re at least living off of their savings and not being a drain on society. Perhaps when they were younger they should have loaned some money to a baby and then they could justify their retirement by having that (ex-)baby pay them back…

Differential earning ability over the course of life means that it makes sense for those in the prime of adulthood to take care of others. We pay-it-forward by taking care of children, and pay-it-backwards by taking care of seniors. This payment could be the result of familial good-will, explicit loans, or institutional welfare. But regardless of the source, it’s wise for society to transfer resources from those at an age where they can work to those at ages where they can’t.

Conservatives might argue that families and explicit loans are a much better way of taking care of the old/young. Families are better than big institutions at deciding whether someone actually needs help and how much help they need due to proximity and closeness. And in a system of explicit loans there’s market pressure that picks out the most promising children and rewards the most savvy elderly, making society more meritocratic.

I think these arguments are basically correct, as far as they go, and I think they’re good arguments for why familial and private support are an important part of the support web. But I don’t think they’re enough to solidly rule out other mechanisms for social support. A thought experiment that I think helps demonstrate this is to step behind John Rawls’ veil of ignorance for a moment and consider whether an unborn child, if given the opportunity and intellect to make good decisions, would want to buy insurance for the life they’re about to have. The way this insurance works is that if the child is born into an abusive or impoverished family, or if they’re born with significant genetic diseases, they get a major pay-out that means their life merely sucks instead of being a total disaster.

This line of reasoning is perhaps even clearer if we take the other side of life and consider retirement. Do those saving for retirement tend to make investments that have the highest expected returns? Nope! Nor should they. The wise way to save for retirement (below a certain wealth level) is to be conservative, investing in low-risk options like bonds and otherwise diversifying one’s assets to further reduce risk.

Insurance and diversification in investing both follow the same logic: the difference in value between having $100k instead of being broke is much greater than the difference in value between having $100k and $200k. More formally, the value of resources tends to scale (approximately) logarithmically for each individual. And when returns diminish, insurance is a good deal even if it costs money, in expectation. The insurance purchaser is transferring wealth from timelines where things go well into timelines where things are a disaster.

I thus suspect that in just the same way as it’s wise to diversify a retirement fund, it’d be a good deal for babies to buy insurance that counteracts the genetic/familial lottery. But note that this insurance cannot be provided by families and markets! If a family is poor, no insurance provider in their right mind would sell them insurance that paid out if their baby was born to a poor family.

There’s a general lemons problem in insurance: when one party knows more than the other, insurance doesn’t work. If life-insurance buyers knew exactly when they were going to die, they could wait until the last-minute to buy insurance. But then life insurance sellers would notice they were losing money and refuse to sell. On the other side, if life insurance sellers knew when people were going to die, they’d simply refuse to sell to those who were going to die young, eliminating the value for buyers. It’s only because neither the buyer nor the seller of insurance know what the outcome will be that it has positive expected value for both of them.

Life is weird. Disasters happen that nobody saw coming. I claim that nearly everyone would be wise to have insurance that protects against disasters in general. But due to the naturally under-specified nature of disasters making enforcement of contracts impossible and the information asymmetry making insurance unprofitable, we need another kind of thing to play the same role. It shouldn’t be a family, or even a local community, because disasters and bad outcomes tend to hit local groups all at once. No, I claim that this is a service that is best provided at large scale, ideally by a universal government.

Welfare in Practice

One of the biggest obstacles to evaluating whether state-run welfare programs are good is the presence of confounders. The nation that spends the largest chunk of income on social welfare is France, which is a pretty good country to live in, all things considered. But is France a nice place to live because of the welfare state, or is there a welfare state there because it’s a nice place to live? Perhaps they’re both downstream of being a liberal democracy, or a country with a high tax rate?

One fascinating change over the last hundred years is the rise in state spending. In 1910 the USA spent approximately 3% of GDP on government expenditures (welfare + pensions + infrastructure + military + debt + salaries + other services). In 2010 that number was 45%. And the USA isn’t a total outlier here. France went from 13% to 59% over the same period. Governments have become much, much bigger.

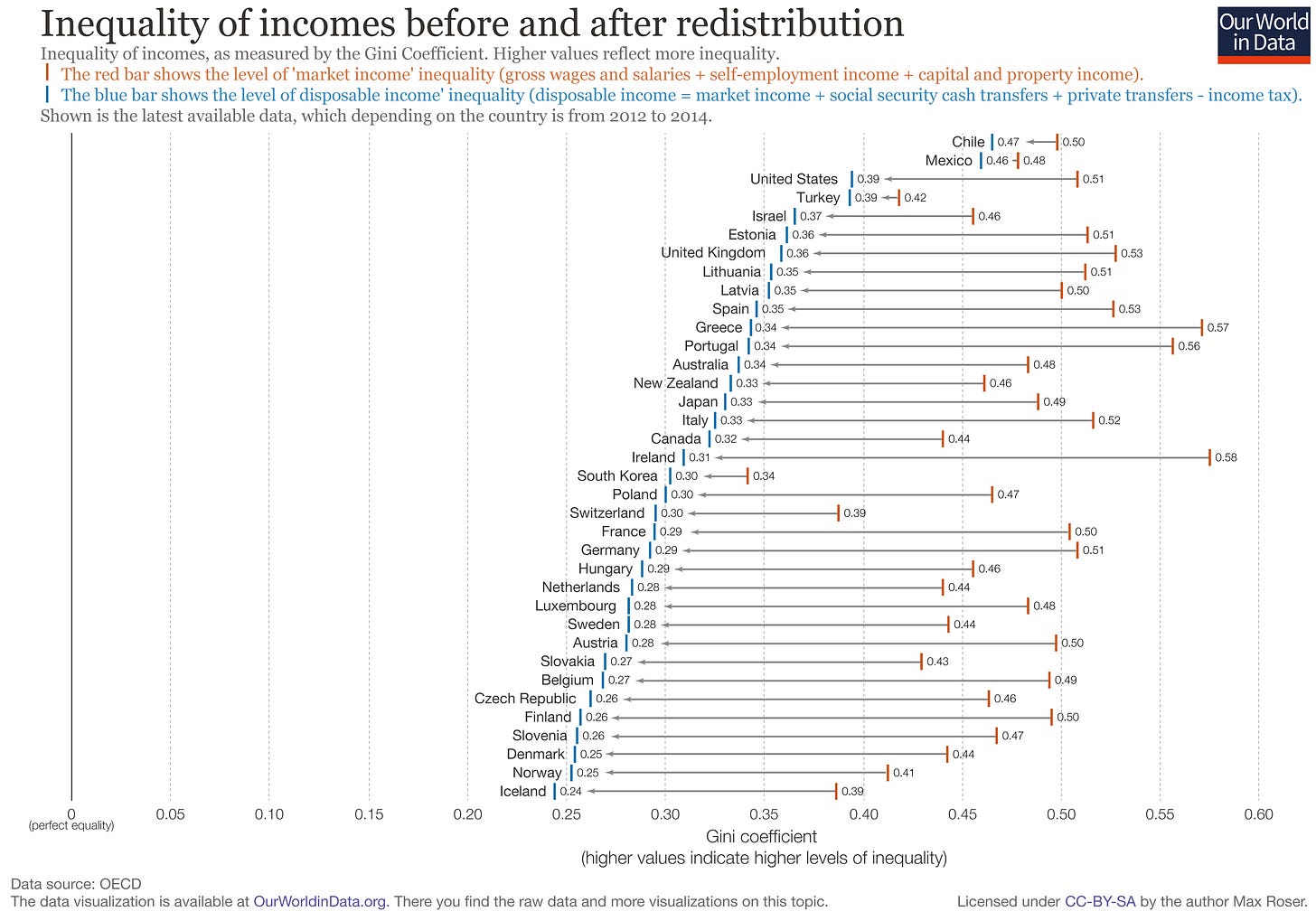

And with this rise in state spending there’s been a corresponding rise in social welfare programs. If we looked at the bar-graph above but for the year 1910 it would be basically non-existent in comparison. The largest state spending on social welfare in that year didn’t even go above 1.5% of total production.

Of course, the 20th century was also absolutely amazing in terms of the growth of wealth. Were big governments to blame for the overall prosperity? Perhaps a little, but I generally don’t buy it. I’m particularly skeptical that welfare itself was driving the rise in wealth. But I also disagree with critics of welfare programs that argue that the money put towards helping the poor is wasted and/or somehow hurts the large-scale economy.

My best guess is that social spending has a bunch of little effects in different directions on total wealth. Yes, those on the dole might not feel the need to look for work. But those taken care of by a social safety-net also might use that support to invest and make better choices, such that when they find work it’s more productive. Again, I don’t really see large-scale impacts from these programs in either direction. Instead, I think it basically just makes sense to think of welfare programs as a transfer of wealth and resources with little net impact impact on the economy as a whole.

We can easily see wars and revolutions in the arc of the prosperity data. The Bolshevik revolution, the great depression, WW2, and the collapse of the USSR are particularly striking downturns. After disaster there is usually a rapid recovery, and in many ways I think it makes sense to model the meteoric rise of China and other similar nations as a kind of recovery-growth following in the slip-stream of the west. Economic policies can be impactful, especially in creating short-term damage. But the long-run trajectory of western nations approximately matches what one would expect, fitting a hyper-exponential curve to data from the 1700s and 1800s. Changes to social security aren’t really visible at the scale of national production.

But these programs do make a difference! …just not to overall output. If we look at inequality (as measured by Gini coefficient) it’s easy to see change in the 20th century with prominent differences between western nations:

The basic story of civilization prior to the 20th century was that there were two groups of people: elites/lords/nobles and commoners/peasants/serfs/slaves. Even as the industrial revolution started generating obscene amounts of wealth (relative to all earlier time periods), this inequality persisted, and in many cases grew. New money industrial barons began to take power from old-money aristocrats, but meanwhile the yoke of the common people more or less just changed hands.

But all this changed in the 20th century, probably due to a coincidence of wars/upheavals and a surge in democratic big-government (along with progressive income taxes). Suddenly there was a real middle-class, not just on the frontiers of the American west, but all over industrial societies.

Now, it might be that the presence of progressive taxes and large welfare states simply happens to coincide with the rise of the middle class. New technologies emerged, trade became global (though these two are often linked to higher inequality), and there was a radical change in the balance of rural/urban living. But as we can see from U vs L-shaped curves in the earlier graph, there was a divergence in income distribution between countries like the UK and USA compared to countries like France and Japan that happened sometime in the 1970s. What happened?

My best guess is Reaganomics (“Thatchernomics” for the UK?), but honestly I’m unsure. In 1927 the top 0.1% earner made about $2.3 million dollars a year, adjusted for inflation (~$150k at the time). On that income they paid a little less than 25% in income taxes — the highest tax bracket at the time. Here’s a graph of the rate of the highest tax bracket that such an earner (adjusting for inflation) would be in over the years:

Reagan’s responsible for the tax cuts in the 80s, but under the narrative that the inflection point was in the 70s perhaps a change of attitudes around money during the years of stagflation was upstream of both Reaganomics and the decrease of financial equality in the English-speaking world.

In the scope of history we can see that whatever happened wasn’t necessary to maintain growth. The GDP/capita lines are quite smooth for that period, even in France, Japan, and Sweden. And as we saw in the first graph of this section, the countries that managed to keep the economic equality of the 60s are the ones that spend a lot on helping the poor.

Utopian Welfare

While there are specific mysteries still to solve, I think the data and science is pretty clear: some kind of welfare is good for society. Welfare helps reduce poverty and inequality without harming the ability for a society to produce wealth, at least at the levels explored by most western nations.

I believe that Utopia is a welfare state, not merely content to sit by and watch some individuals and families accumulate immense amounts of wealth while others break their backs engaging in subsistence farming and struggle to find enough to eat. Utopia doesn’t try to make everyone equal — just to protect everyone from starvation, homelessness, disease, and violence.

In Part 2 I address why I think a basic income is the right way to do this.

“Too many people ... haven't had the chance to pursue their dreams because they didn't have a cushion to fall back on if they failed... We should explore ideas like universal basic income to make sure that everyone has a cushion to try new ideas.”

— Mark Zuckerburg (2017)