Energy (Part 1: Renewables)

TLDR: Solar and wind power are awesome at the current margin, but will ultimately need backup in some parts of the world.

Prerequisites: None

Which is more valuable: water or diamonds?

This classic economics riddle revolves around the difference between total value and marginal value. Without water, life on Earth would be impossible, and the same cannot be said of diamonds. Therefore water is more important on the whole. But if you have the opportunity to create a kilogram of water or a kilogram of diamonds, the extra diamonds are vastly more valuable in the current world. We have plenty of water — diamonds are scarce.

In our current world the hands-down best source of energy is solar photovoltaic panels, with a runner-up of wind turbines. Solar and wind power are amazing. In my lifetime I’ve watched both technologies go from pricey niche options for the ultra-eco-conscious to mainstream, efficient energy sources. We’ll get into the specifics of that in a moment, but as we do I want to keep in mind that we mostly have data for the current margin. As we build out new solar panels and wind farms the world will change. Some of these changes can be seen by looking at the trends in renewable energy over time, and some have yet to manifest.

Okay. Onto the data!

Just look at that growth curve! Both solar and wind power are growing at an exponential pace. The doubling-time of wind production looks to be about 6 years, while solar energy production has been doubling nearly every 3 years! What has been driving this change? Well, mostly technological improvements, the spread of knowledge, and economies of scale. See Our World in Data for more.

It gets better: we’re probably not at the bottom of the price roller-coaster for renewables! As we get more wide-spread adoption, we should expect the relative price of energy to continue to decrease. Decreases in price mean more adoption, which mean bigger markets and more research, which means lower prices. 🎉

This is a huge deal, especially for poorer parts of the world. For many years it was assumed that poorer areas would need to burn comparable quantities of fossil fuels to bootstrap their economies and reproduce the development done by nations that industrialized earlier. But low-cost renewable energy will likely mean that the economical thing to do in various parts of the world (especially Africa, where both wind and sunshine are plentiful) will be to jump straight to renewable energy.

But of course, in addition to now being affordable and well-tested, solar and wind energy are extremely safe and good for the environment compared to almost every other energy source. Fears about wind turbines being bad for birds are overblown (sorry), and in the rare instances where we want to prioritize the safety nearby eagles, etc, we can use vertical axis (VAWT) designs. Similarly, the greenhouse gas emissions from manufacturing and the number of accidents from installation and maintenance of solar and wind generators are very low, in the scheme of things.

But y’know what sources are really bad for the environment and kill a LOT of people?

And do you know what sources we use a LOT, as a species?

It might look extremely daunting to overcome fossil fuels with solar and wind. In the graph above, they’re a barely perceptible sliver on a mountain of polluting carbon (and a blanket of nuclear and hydro). But in fact, this is good news. 87% of greenhouse gas emissions come from burning fossil fuels for energy, so if we could make solar and wind explode, they could perhaps solve almost the entire problem. And they’re currently set up to do just this — exploding in magnitude in coming years. This is what exponential growth means! What seems tiny one year can turn into a landslide just a few years down the line.

According to one dataset used by Our World in Data, 2022 Earth consumed about 11,000 TWh of renewable energy, and that number has been growing at an average of 12.8% annually since 2011. If we extrapolate that curve outward, it’ll take 22 years for renewable consumption to be ~156,000 TWh, which is more than all fossil fuel consumption this year, and by 2050 we’ll be collectively producing over 321,000 TWh, which is certainly enough to dominate all fossil fuel use, even accounting for increased demand.

We have to be careful about reasoning about exponential growth, however. At some point the exponential turns into a sigmoid, and progress starts to slow down. If it didn’t, then in 500 years we’d be consuming more power than is produced by all the stars in the galaxy. Perhaps we’ve been on a particularly fast-growth trajectory, and we’ll start slowing down soon.

It’s important for the health of our planet and species that we keep up the pace. So let’s explore some reasons why renewable energy might fail to solve all our energy problems in the next thirty years, and what we can do to help keep things on track.

It’s not always sunny in Philadelphia

Half of the time it’s night. Much of the time the wind doesn’t blow. Unlike hydro, tidal, and geothermal, the power generated by wind and solar changes based on time of day, time of year, and the chaotic weather.

At the current margin, these concerns aren’t a big deal in most places. Peak electricity demand right now is in the summer afternoons when people run air conditioners, and solar panels naturally provide their energy during that time. But thanks to falling costs and other exponential trends, we’re about to have a lot of solar panels. As solar becomes more and more of the energy supply, summer daytime power will become cheap, while winter nights stay expensive. In that world, an additional solar panel doesn’t help that much, and energy producers will still be temped to lean into options like natural gas.

In order to continue to have power during periods of low supply, we need cheap, high-capacity energy storage. Our current best bet here, at least for smoothing out the day/night cycle and for when the wind doesn’t blow for a couple days, is to use batteries. Lots and lots of lithium-ion batteries. Much like the price of solar panels, the price of batteries has been dropping exponentially.

As people switch to electric vehicles and install solar panelling on their roofs, large batteries will become common in most homes. All it takes is a little bit of smart-grid, and people will naturally be charging those batteries in periods of highest-supply, and selling energy back to the grid when the demand is highest. Market forces to the rescue!

But perhaps we need more storage than traditional batteries can provide. After all, the difference in sunlight between the summer and winter in many places is enormous, and we don’t want cities to fail if the winter wind in those places is calm for a week straight. There are a fleet of interesting technologies on the horizon, most of which I’ll simply ignore as too-speculative, but the two other heavy-hitters in the space of long-term storage that I want to explore are hydrogen and pumped hydro.

I’m moderately more bullish about pumped hydro storage for a couple reasons. In a pumped hydroelectric plant, during times of peak supply water (or occasionally a denser fluid) are pumped up a steep incline to a reservoir. Then, when energy supply is low, the pump inverts and the water pours down the slope, turning a turbine and generating power. Pumped hydro plants have been around for a long time, and are a well-proven technology. Even including lithium-ion batteries, pumped hydro accounts for over 94% of the world’s energy storage capacity! Furthermore, a reservoir can in principle be kept filled for months, theoretically allowing energy to be pushed from summer to winter.

The main downsides to pumped hydro are the need for a lot of land for the reservoir and the need for a sharp change in elevation near a river/lake with considerable volume. If we’re talking about providing energy storage for months, we’re talking about building and maintaining truly colossal reservoirs. In contrast, hydrogen storage (and most other methods, like batteries) require much less land and can be put in more places.

In a hydrogen power storage facility, cheap electricity is used to break water down into hydrogen and oxygen gas. The hydrogen can then be captured, either as pressurized gas, cryogenic liquid, or (possibly) by embedding in metal. In theory, the process that converts water into fuel and back again could be used for desalination, in parts of the world where fresh water is scarce. Unfortunately, the efficiency of hydrogen setups is often quite bad compared to other options, due to the costs of pressurization, cooling, etc.

It’s possible that new technologies might make hydrogen efficiency improve. And if we’re talking about storage that can last for months, low efficiencies might not even matter, as hydrogen power could kick in only when battery and pumped hydro sources are dry.

Overall, I’m not concerned that energy storage is a sticking-point for wind/solar power on the scale of hours and days. Power during the dead of winter in the far north might be tricky, but that’s ultimately a small portion of the globe. While skeptics like to point out that the sticker price of solar usually doesn’t include the substantial cost of storage, I think in practice the exponentially falling costs of various storage options, combined with the advent of new technologies (including smart-grids and better weather-prediction) will mean we can find at least partial solutions to our storage needs over the coming decades.

It’s always cloudy in Pittsburgh

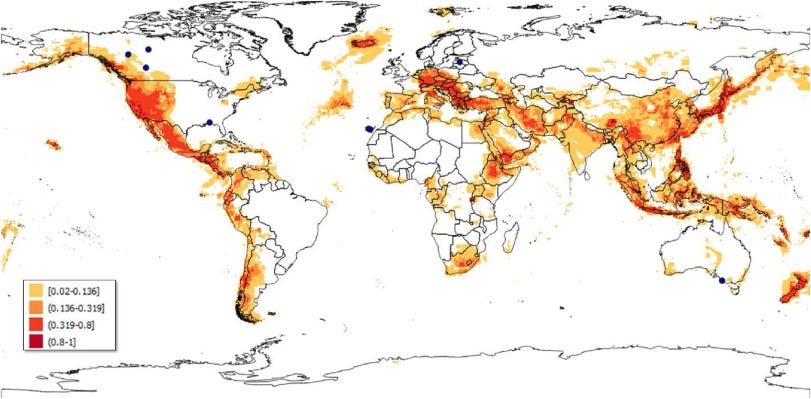

As I mentioned, solar power in the far north is far less attractive than in the tropics. Likewise, there are places on Earth where wind energy doesn’t make much sense, and the same applies for hydro, geothermal, and tidal power. In fact, the location-specific nature of these last three renewable sources is what makes them less interesting as far as global solutions are concerned. Here are a pair of neat maps, illustrating the potential of solar and wind power across the globe:

As can be seen, many places have a high potential for solar power, and many low-solar coastal regions such as Ireland, Alaska, and Norway have a lot of potential in wind. The worst-off region looks to me to be China and some of Oceania. Indeed, this is quite bad, as that region accounts for billions of people.

It gets a little better when we bring geothermal energy into the picture.

Unfortunately, we don’t have the same trends of exponentially improving efficiency and price for geo that give me hope for solar and wind, but Indonesia and the Philippines are indeed world-leaders (just behind the USA) in geothermal production.

Hydroelectric power also gives some hope for China, though with so many people increasingly hungry for energy, I admit that I’m concerned that renewables will fail to entirely satisfy some high-demand areas.

Electrical grids can span vast areas of the globe, spreading out load in ways that make things remarkably robust. Even in low-solar areas like Scotland it can be sensible to get photovoltaic cells to capture production in summer, and certainly there are lots of places in China where solar energy is plentiful much of the time. Perhaps that, combined with hydroelectric and some geothermal power, will allow China to find energy independence through renewable resources alone.

But perhaps the total capacity of renewable energy won’t get us to the targets we need to hit to make climate change a problem of the past. If this is the case we’ll need other sources of energy to serve as a backstop in the winter, at night, and when the wind is calm.

Here’s where nuclear fission enters the picture, in my view. With a healthy dose of nuclear energy, China, and perhaps all countries across the world, can become even more robustly post-carbon. I’ll explore nuclear energy in Part 2, and talk about Utopia in Part 3.