Laboratorists

TLDR: Science would be better served by cleanly separating those who do theory from those who do experiments.

Prerequisites: None

Bias is a real problem in science. It’s extremely common for a scientist to come up with a clever theory and then set out to prove themselves right. The act of trying to prove oneself right is antithetical to good scientific rigor, but it’s a very understandable stance. Being right means fame and fortune, while being wrong can mean wasted effort and possible embarrassment.

In theory, science is about the process of learning about the world, including learning what’s false, so a scientist who does nothing but criticize others should be just as laudable as one who spends their time cooking up new hypotheses. But in practice this is simply not true. The most famed historical scientists (Newton, Darwin, Einstein) are mostly famous for developing new theories, not debunking old ones. We talk about cold-fusion by citing Fleischmann and Pons, who cooked up a shoddy result, not Nathan Lewis who valiantly tried, but failed, to replicate it (his Wikipedia page doesn’t even mention cold fusion). We talk about phrenology primarily by introducing Franz Joseph Gall, the pseudoscience’s pioneer, not Marie Jean Pierre Flourens and Paul Broca, the experimentalists who demonstrated its falseness. (Much like Einstein, etc, when we talk about Broca, we usually reference him in terms of his contributions to modern theories, rather than for the false theories that he defeated.) Even the scientist who is perhaps the most famous debunker of all time — Louis Pasteur — is most centrally championed as one of the fathers of the germ theory of disease and for his role in developing theories of vaccination and pasteurization.

Is it any wonder that young scientists aspire to be creative rather than critical?

And the incentives don’t come anywhere close to stopping there. Negative results are routinely discarded, rather than published. Scientists rightly fear that putting in work to put out a paper that basically just says “I tried this and didn’t get anything interesting” will be an uphill battle for little reward. And even when a negative result or a failed replication is a knockout punch to an existing theory, publishing something that actively attacks the work of other scientists can create political and social turmoil that can sink a career — especially if the counter-evidence is coming from a young scientist and aimed at an established group of seniors.

Bias, Bias, Everywhere

The problems with theorists trying to prove their pet theories should be obvious. First, there’s a risk of outright fraud, which happens remarkably often. A 2022 study in Amsterdam found that (under strict anonymity) over half of scientists surveyed admitted to engaging in some questionable research practices such as fabricating data, unjustified speculation, sloppy methodology, selective reporting of data, or leaving out known counter-evidence. And this is what the scientists are conscious of and willing to admit! Subconscious bias is almost certainly more prevalent, nudging researchers to turn their eyes to see what they want to see.

Bias is the reason why practices such as blinding, pre-registration, and randomized controls are the gold standard in research. But even these are insufficient, especially when it comes to communicating scientific results (even among scientists!). The replication crisis has been an important wake-up call to many scientists and disciplines, and now, as a society, it’s time to hold ourselves to a higher standard.

What would it even look like to hold science to higher standards than pre-registered, peer-reviewed, blind, randomized, controlled trials? Well, it seems to me that a good start would be to change who does experiments in the first place.

Utopian Laboratorists

In my ideal Utopia, “scientist” is a catch-all term for two groups of people: theorists and laboratorists. A theorist’s job is to look at the world, data, experiments, etc. and form hypotheses that elegantly explain how things work. A laboratorist’s job is to try and produce the highest-quality data, either through meticulous recording of the natural world or careful experimentation. This separation — between theory and observation/experiment — means that no scientist ever (publicly) tests their own theory.

When a theorist publishes a paper, it has analysis of existing data, proposed mechanisms, and then sometimes one or more proposed experiments. Proposed experiments are often far more detailed than an average Methods section from our world, because theorists know that any subtle details they omit from their proposed experiment are unlikely to be implemented by laboratorists who try to test their hypothesis.

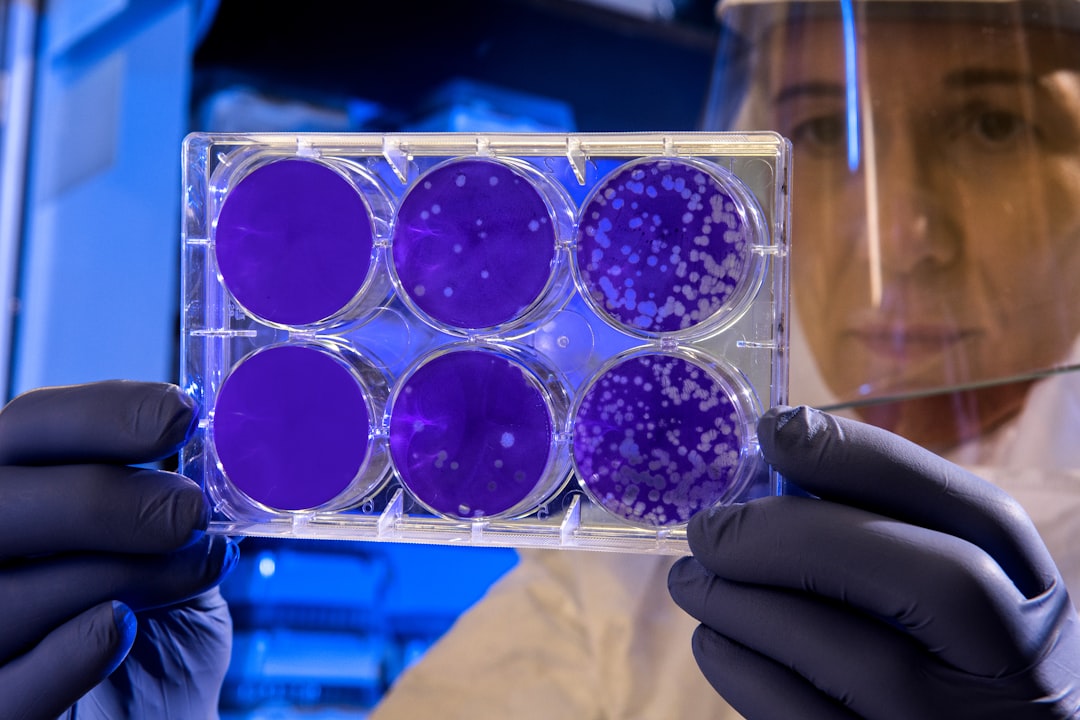

Laboratorists, meanwhile, don’t exactly “publish papers.” Instead, they publish datasets. The mark of a good lab is that their data is meticulous, rich, and well-supported by a full description of what they did to collect it. Laboratorists pride themselves on replicating each-other’s experiments and observations, sometimes competing for attention and funding by how well their data can be corroborated by their peers. Good labs are transparent, keeping data on every experiment they run, and publishing everything they get, including when errors happen (noting that the data reflects the error).

Utopian labs almost never allow the experimenters themselves to know anything about why the experiment is being run. A lab manager evaluates the state of the field, on the lookout for proposed experiments that could be run or high-controversy opportunities, and writes up a detailed methodology that will be published alongside the data. The laboratorists then follow the methodology to the letter, deliberately blind to what hypotheses are being tested.

Being a laboratorist is an honorable profession in Utopia, with a history of famously hard-headed scientists who dedicated their lives to data collection and experiment. Labs are funded in the same way other journalists are — a combination of paywalled content, patronage, and retroactive funding. Because they don’t need to show statistical significance of anything, small labs or individual laboratorists can thrive in Utopia if they have good, interesting data.

The division between theory and experiment helps protect science from bias, leading to a clearer view of reality with more open data and replicable experiments.