Writing

TLDR: Utopia has a global language (in addition to many local, cultural languages) that uses a phonetic alphabet designed from first-principles to be able to faithfully represent all sounds and easily able to be read/written/learned. It does this through a scaling system of diacritics. A proposed version of the basic form is presented here.

Prerequisites: None

Foundational to: Numbers

One of the most common utopian dreams is that of a universal language for all of humanity. From Leibniz’ Characteristica Universalis to Zamenhof’s Esperanto, from the biblical the language of Eden to 2019’s Globasa, thinkers throughout the ages have craved a single tongue to unite the world.

This makes sense. Language is a fundamental part of social cohesion and cooperation. The barrier of language divides societies and stands in the way of a united world. If everyone spoke the same language, trade in goods and culture could skyrocket and usher in a golden age.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not a proponent of everyone only speaking one language. I think the multitude of languages is very cool, and the death of languages is sad. Languages carry culture and heritage — they serve as a way to bond with our kin, both in the present and in the past. Each natural language is like an organism, with its own sounds, concepts, and perspectives. There is no replacement for the forgotten poems of the dead.

But having a diversity of cultural languages is not mutually-exclusive with sharing a language with those on the other side of the world. Around 60% of the world can speak more than one language. It seems wise for everyone have a home-tongue that’s used within their family and cultural-group, and a world-tongue that lets them communicate with everyone else.

The project of crafting, teaching, and maintaining home-tongues seems best left to each specific culture. But the project of having a perfect universal language is right up my alley, and the rest of this essay will be devoted to beginning on the journey of building a Utopian writing system (alphabet, etc.) that could be used by all humans, now and into the future.

Guiding this exercise in design will be a few core principles:

No Legacy Code — A truly Utopian language is optimized not according to what’s come before, but how a perfectly ideal society would communicate.

Pragmatism — Leave the flowery poetry and fancy calligraphy for home-tongues; our Utopian language should be really good for airport signs and legal documents.

Neutrality of Time and Place — Universality means having a language that works well for as many people as possible, including those to come; this means not assuming speakers live on Earth or that they’re even human (though we need to assume they have human-like mouths and hands to make any headway).

Warring Goals

There are two primary conflicts that we need to navigate as we jump-in to designing a Utopian writing system:

Reading vs Writing

Some symbols are easy to distinguish with the eye. Contrasting shapes, colors, thicknesses of lines, and prevalence of sharp details help readers tell what a word is at a glance.

Other symbols are easy to make with a stylus. Lines of a single color and thickness that glide into each-other are fast and efficient to write.

Universal Inclusion vs Universal Accessibility

There’s a kind of privilege to having one’s name be readable and writable in a given script. It would be great if our neutral writing system could serve as an international phonetic alphabet.

No language on Earth includes all the sounds and ways of speaking that are present in every language. Trying to capture everyone’s sounds would result in an overly-complicated language that nobody could faithfully reproduce.

To move towards resolving these tensions, I want to note that they rhyme with each-other in a way. Optimizing for reading and inclusion means being complex, while optimizing for writing and accessibility push towards something simple.

Here’s my proposal: there should be a basic script that’s optimized for writing and capturing distinct sounds that are in almost all languages, but there should also be a way to decorate letters so that they capture more and more details, to the point where words in any language can be faithfully represented. Keyboards could be optimized around producing basic characters, with computer software using context and hints to automatically flesh out letters to be more specific, and easier to read.

Another point of tension is how the writing should flow. Some languages go left-to-right, while others choose right-to-left. Here the answer is straightforward. Just like in English, individual letters should be written mostly vertically (or perhaps italic), words and sequences of words should go left-to-right, and lines of text should be oriented top-to-bottom (and then front-to-back). The logic here is not Anglo-centric; English (and Latin) just happened to get it right. Reading is approximately equally easy in any direction, but writing some ways is easier than others. The fastest movements when writing are with the fingers, which move up-and-down more easily than side-to-side, making vertical orientation correct for letter details. Words are denser if the letters are juxtaposed orthogonally to their orientation, making side-to-side the right way for words. Most people are right-handed, and are likely to smudge ink/graphite if writing right-to-left or bottom-to-top. (And it’s more natural to peel back layers of a book, rather than successively apply them.)

Finding Basic Overlap

In order to find an inventory of sounds to go with the letters in our basic script, let’s compare Earth’s most spoken languages for a moment. They’re “legacy code,” but the distribution of sounds in these languages is some evidence of what sounds (phonemes) humans find naturally easy to distinguish/pronounce. If we can find commonalities, they can serve as the basis for our (simple) alphabet.

Let’s compare English, Modern Standard Arabic (MSE), and Standard Mandarin Chinese. English distinguishes a wide range of vowels largely through mouth-articulation, while MSE distinguishes largely on length, and Mandarin on tone. If we look at what sound-groups are distinguished across all those languages (and ignore glides for now) we get i (“me”), a (“ma”), and u (“moo”).

Almost all languages use nasals, and distinguish between m and n. Likewise, almost all languages have plosives, though distinction through voicedness or aspiration is spotty; it seems good to have three basic families of plosives corresponding to p/b, t/d, and k/g. Languages are all over the place with “r” sounds, and some (like Japanese) fail to distinguish it from “l”, making me think that there should be one basic letter for l/r. As far as fricatives go, most common languages seem to have at least one sound in each of these clusters: f/v/θ/ð, s/z, ʃ/ʒ, and h/x. (ʃ = “sh” in “ash”; ʒ = “ge” in “mirage”; x = “ch” in “loch”).

I think it’s also important to include a letter for the cluster of click sounds. While these are basically absent from most languages, they are still (fairly) easy to make and recognize. English uses clusters of letters like “tsk” or “tick-tock,” but really they deserve a letter to themselves so that they’re represented as distinct (which they are).

Finally we have the glides, like we hear in “yes” or “west,” and the affricates, like at the start of “jump” or “chew.” While glides are common across languages, and affricates are hardly rare, it seems needlessly complex to add them as distinct letters, rather than build them out of combos of letters that already exist. For instance, we could approximate “yes” using the basic letters ies and clarify potential collisions with other words using advanced script marks in the same way we’d distinguish the s from a z.

Basic Orthography

With this inventory in hand, we must turn to the task of finding an optimal set of symbols to represent our basic letters. Reminder: these symbols should be easy to write, provide room to be decorated to make advanced/specific letters, and be primarily vertical.

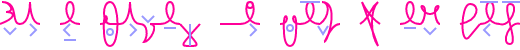

In my design I’m attempting to have a fixed-width set of characters to help guide the eye, where each word can be written with a single unbroken line, and the shape of the letters is a clue to how they’re pronounced. Variable-height letters seem good, to provide diversity. The letters in the alphabet are ordered to put consonants first and follow a natural chain of sounds based on manner and place.

Let’s start with the nasals. I’d like both letters to be smooth and big, going above and below the start/end line, with obvious similarity to each other, but still visibly distinct. The first nasal (written as “n” in latin) and covers the non-labial consonants, while the other (written as “m”) covers labial consonants.

Next come the pulmonic plosives. We want to match the order of the nasals, so our plosives are dorsal (“k/g”), followed by coronal (“t/d”), followed by labial (“p/b”). To match their sounds these letters should be sharp, rather than flowing:

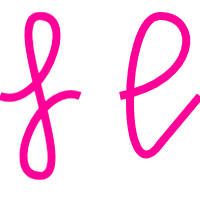

Proceeding to other obstruents, we encounter the fricatives. Let’s begin with the non-sibilant fricatives in “f/v/θ/ð” and “h/x”. (Due to poor planning, I also put the symbol for “l/r” in the image below, but I want that letter to come just before the vowels, and will discuss it later.) The letter for “f/v/θ/ð” is soft, but clearly distinct from the nasals. I’ve chosen a straight line for “h/x” to capture the neutrality of the mouth when making the sound.

And next we have the sibilants: “ʃ/ʒ” (like in “ash” and “mirage”), and then “s/z”. These letters resemble each other and resemble the “f/v/θ/ð” fricative.

The last (normal) consonant covers all vibrants/liquids, which in english covers both “l” and “r.” The symbol for “l/r” (seen earlier, due to poor planning and lack of desire to mess with the images again) is intended to be similar to (but still distinct from) the vowels.

Speaking of vowels, our vowels are also arranged from back-to-front: “u,” then “a,” then “i.” I tried to make “u” particularly round, and “i” particularly sharp.

And lastly we have the letter for clicks and other non-pulmonic sounds. To emphasize the abrupt, distinct nature of these sounds, I went with a single vertical bar:

An english pangram for this alphabet is “Be a she-gull who said ‘tsk’ of men.”

Advanced Orthography

The basic letters don’t have specific pronunciations; symbols in the basic orthography are deliberately broad and ambiguous. It wouldn’t be technically incorrect (just dumb) to read the pangram from the end of last section as “Peh, uh, sheeker who sat *pop* ‘ave mang.”

To clarify exactly what we’re saying, diacritics can be added to our letters. Diacritics are often faded or in a slightly different color than the primary letters. While specifying the entirety of the diacritic space would go beyond the scope of this particular essay (and be boring), let’s at least hit the main marks that will narrow-down sounds to the phonemes that are particular to English.

Let’s start with voicedness: one of the properties that distinguishes “p” from “b,” “s” from “z,” et cetera. You can feel voicedness by putting your hand on your larynx and saying different sounds. Unvoiced sounds are smooth, so we’ll mark them with a small circle (like ◌̥) that hangs out near the middle-line in the center of the letter. In letters like “p/b” it hangs out below the letter, and in “k/g” it hangs out above. Voiced sounds vibrate, so we’ll mark them with a small downward-pointing chevron symbol (like ◌̬) that appears in the same spot the voiceless diacritic would go.

Next, let’s consider relative place of articulation. An overbar on the letter (ideally in a thinner line style or slightly different color) indicates a letter’s sound is closer to the lips, while an underbar indicates closer to the throat (this matches a general pattern in the letter forms). This can be used to distinguish “n” sounds (overbar) from “ŋ” sounds (like “ng” in “sing”) (underbar), or “f/v” sounds (overbar) from “θ/ð” sounds (like in “thin” and “this”) (underbar).

An “x” inside the hoop of “l/r” indicates a rhotic “r” sound, while a vertical line that cuts the letter in half indicates a lateral “l” sound.

Finally, we get to vowels. Vowels are characterized in many ways, and again we’ll avoid most of the specifics. Instead, let’s just cover the most common english vowel sounds:

ɪ (“i” in “sit”) = “i” letter with a left-pointing chevron beneath

i (“ea” in “seat”) = “i” letter with an right-pointing chevron beneath

ə (“u” in “upon”) = “a” letter with an right-pointing chevron beneath

ɛ (“e” in “dress”) = “a” letter with overbar

æ (“a” in “cat”) = “a” letter with overbar and left-chevron beneath

ʌ (“u” in “bun”) = “a” letter with underbar

ɑ (“a” in “palm”) = “a” letter with left-pointing arrow and underbar beneath

u (“ou” in “soup”) = “u” letter with an right-chevron beneath

ʊ (“oo” in “foot”) = “u” letter with a left-chevron beneath

aɪ (“ie” in “pie”) = “a” + “i”

eɪ (“ay” in “may”) = “i” with left-pointing arrow beneath + “i”

oʊ (“oa” in “goat”) = “u” with left-pointing arrow beneath + “u”

aʊ (“ow” in “how”) = “a” + “u”

Utopian Writing

While it may take work to learn multiple languages, I think Utopians put in the effort. In addition to the language and alphabet of their ancestors, Utopians learn a global language with its own alphabet that’s been designed to have good properties such as a collection of simple letters that are easy to jot down notes with, but which can be annotated to capture precise sounds.

Using this alphabet, Utopians have a much easier time pronouncing words in books, even when they’re names from a distant land.