Determinism

TLDR: Utopians are determinists who accept the many-worlds interpretation of quantum physics.

Prerequisites: Having read Spacetime Distances will help, but isn’t strictly necessary

One of the longest-running debates in philosophy is about whether our universe is deterministic. In a deterministic universe the future (and possibly the past) is a mathematical consequence of the present moment. Or in other words, if we somehow knew everything about the state of the universe at some particular time (along with all the laws of physics) there would be nothing else to learn; all other facts of the universe could be derived.

Of course, “could be derived” is leveraging a very strong notion of “could.” No actual being can ever have full knowledge of the universe, much less compute its future in perfect detail. I’ll be a bit loose with the word “could” in this essay, as I think it makes the language more natural and concise, but please keep in mind the limits of what physical minds can ever know.

Note that knowledge of the past/future is different from building the past/future. “Building” implies that there’s an action being taken in time, but in this case the thing that’s being “built” is time itself, which implies a meta-time that God experiences or whatever, such that on God’s Monday He creates the first million years of the universe, on God’s Tuesday He creates the next million years, et cetera. It’s just unnecessarily complicated. There is no meta-time. Events that are elsewhen exist in a timeless sense of “exist,” just like events that are elsewhere.

But that doesn’t mean the concept of being able to reconstruct a complex whole from a simple part is crazy. As a bit of a metaphor, let’s say that I have a straight line in a 2D Euclidian space. If I have any two points on that line (or a single point and a slope), I can reconstruct every other point on that line. In other words, those points determine the full picture. And yet, those two points aren’t special — we could equally easily find those points by knowing a different pair of points and reconstructing the line that way. The point is not that there’s a unique moment that determines all other moments, only that sometimes a fraction of a picture is all that’s needed to fill in the whole thing.

Determinism is a bold claim, pushing against several intuitions and scientific observations. It doesn’t seem true to me that all universes “have to be deterministic,” as some philosophers have suggested. Time is a very specific part of our story of the universe — one that we’ve come to see as very closely related to space. And the universe is certainly not deterministic in space; if a being knew the state of all things that are, were, and will be, but only at a specific point in space, I do not think that being (even with infinite resources) could ever deduce the state of all the rest of the universe.

Still, I am quite firmly on team determinism. I’ve reviewed the evidence for and against, and am quite satisfied that there are both good reasons to be a determinist and strong rebuttals to the nay-sayers. Let’s get into them.

Determinism’s Justification

I subscribe to Bayesian epistemology, so in my mind there are two pillars that justify all knowledge: simplicity and explanatory power. Conversely, there are two modes of criticism for an idea: “that’s more complicated than it has to be” and “that doesn’t fit what we see.” I think determinism does well on both counts.

A deterministic universe is far, far simpler than an indeterministic one. Even in a finite, discrete universe we’re talking immense savings; consider the difference in quantity of data between emailing a movie to someone versus emailing them a single image from that movie. In general, whenever we can rederive something from what we already have, that’s a savings to the complexity of the whole.

This is particularly true if our universe had some kind of “initial condition” that’s particularly easy to specify… such as a time when the whole universe was approximately one point. It seems very plausible to me, though I don’t know enough physics to be sure, that specifying the exact state of the universe in its infancy is actually pretty straightforward.

This perspective also gives weight to the idea that determinism isn’t just one-directional. In some conceptions of reality, the future is entirely determined by the present, but there are multiple possible pasts (or conversely, there is a single past that can be determined by looking at the present, but many possible futures). But for this to work, there either must be an earliest moment that generates everything, or a line in time somewhere beforewhich determinism ceases to hold, or some strange math about infinite regress. All of these are more complicated than simply saying that determinism applies equally to the past and the future.

But doesn’t this argument also suggest determinism in space? Surely a spatially-determined universe is even simpler. Or at the very least we could specify one of the spacial dimensions by referencing things the in other two.

Alas, while spacial-determinism is a simplification, it’s an oversimplification. We can observe time-deterministic physics in everything from the motion of planets and stars to the evolution of quantum systems. Nearly all physical laws are presented in a time-deterministic way, and no serious spacial-determinism has ever shown up in our study of the cosmos.

What does non-determinism look like? It looks like something happening that couldn’t have (theoretically) been predicted in advance. This includes, among other things, certain forms of time travel. If a time-machine showed up unexpectedly, in a way that isn’t determined by the past, that’s a violation of determinism. This doesn’t mean “time-travel” is strictly impossible — we could imagine a “time machine” that was always there, and just happened to (from one perspective) have a “time-traveler” walk into it backwards. But notice that from this perspective it’s a little unclear what it even means for something to “be moving backwards in time.” Indeed, I think determinism is one piece of the puzzle for understanding why we think things “move forward in time,” which is just as nonsensical, in a way.

“The Present”

Readers who are familiar with special relativity (or who read my essay on spacetime) may have an objection to the notion of “the present” determining “the future.” Physics tells us that because we’re free to exchange space with time in a Lorentz transformation (the generalization of a rotation to spacetime) there is no objective truth about which events are simultaneous.

Indeed, it turns out that this makes determinism is even stronger than it would be in a universe with a different notion of time. Instead of there being a privileged perspective from which the universe is deterministic, I claim that all possible reference frames demonstrate determinism. In other words, we can predict the future/past by knowing the state of the universe from your perspective or my perspective!

This is pretty wild, and has some awesome implications. It means that even if I think a clock striking noon happens before a lightning strike and you think a lightning strike happens before noon due to us traveling at different speeds, we can predict the lightning-strike from a time-slice of the noon-first universe, and we can predict the chiming-of-noon from the lightning-strike-first universe.

Indeed, since this applies even at the smallest scales, it means that the immediate change at some point in space can only be a function of the local properties at that point. If how something changed was non-local, then there’d be a perspective in which it changes based on an event in the future, and thus violates determinism. This principle of locality is incredibly important in physics, giving rise to everything from fields to the linearity of quantum operators.

Quantum Determinism

But of course the elephant in the room is quantum mechanics, which famously contradicts determinism, even if we allow for the universe to have hidden variables that we have a hard time observing. Or at least, many people think it contradicts determinism.

In fact, all the laws of quantum mechanics are fully deterministic! It’s merely bad philosophy that’s led to a mistaken view that quantum mechanics are random. (Just as Einstein was rallying against when he said “God does not throw dice.”)

The most famous equation in quantum physics is the Schrödinger equation:

Which tells us how a quantum system (“|Ψ(t)⟩”) changes with time (d/dt) as a function of the measure of energy in the system (Ĥ). There is no room in this formula for randomness, observation, free will, or entities from the future or past. Quantum systems evolve based entirely on the (local) energy-landscape at a particular slice through time.

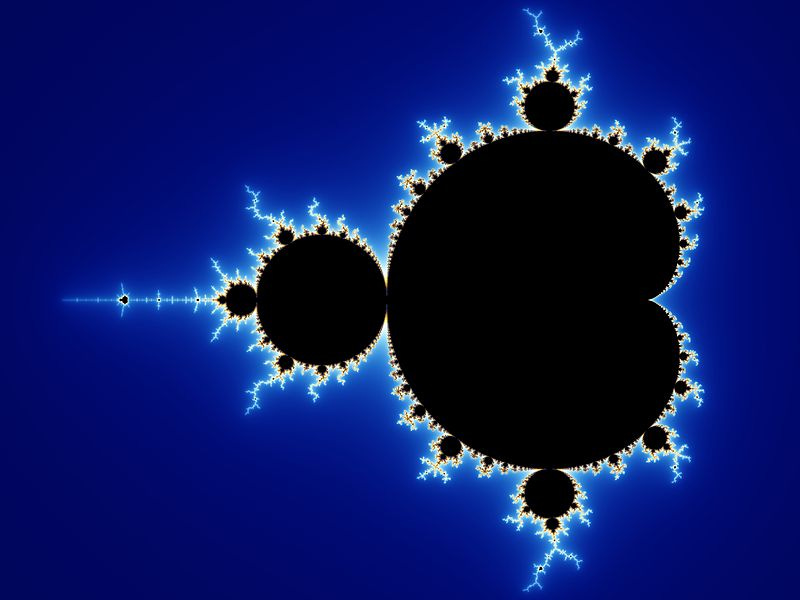

So where does “quantum randomness” come in? Well, unlike classical physics, the “wavefunction” Ψ doesn’t just talk about a single configuration of the particles in the universe — it talks about all possible configurations of particles, including all possible configurations of the atoms that make up human beings. Since your thoughts are essentially encoded by neurons in your brain, then there’s a part of the quantum system where those neurons are in a different configuration and “you” have different thoughts.

I put “you” in quotes there because this is where the bad philosophy usually trips people up. Human beings are made of matter, and matter is governed by quantum physics, so you’re part of a quantum system. But you aren’t localized to a particular configuration. There are a whole host (an infinite quantity in fact) of quantum configurations where it makes sense to say there’s a collection of atoms that compose your body. But you aren’t in any particular body — you’re in all of those bodies.

As an analogy, consider a machine that puts you to sleep and duplicates your body. putting a copy in each of two rooms that are indistinguishable from the inside. When you awake, which room are you in? Whatever you decide to say, both bodies will utter the words. For all intents and purposes it’s correct to say that you’re instantiated in both bodies, and thus in both rooms. If a different sound plays over a speaker in each room, your future splits into two versions. Which sound does “the real you” hear? Well, both versions stem from the same source, and neither is exactly the same as the version in the past. There’s no truth to which is “the real one.”

Just as it is in the analogy, it is with quantum systems. When a quantum experiment is run, some of the bodies that instantiate the experimenter see an outcome one way, and some of them see an outcome another way. Each version of the experimenter may believe that they’re the real one, but in fact “observation” is simply what it feels like to become entangled with the world.

I could go on, but better writers than I have done a good job at explaining the compatibility of quantum mechanics and determinism. Most famous is perhaps is Hugh Everett III, the father of the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. I’m also partial to the writings of Max Tegmark and Eliezer Yudkowsky.

Free Will and Fatalism

Tragically, I think most of the opposition to determinism comes from another bit of bad philosophy in the form of whether we have “free will.” When people encounter the idea that the future is deducible from the past, it collides with a subjective feeling of being able to freely choose between actions. If determinism is true, then couldn’t someone (theoretically) use their knowledge of the past to deduce what my actions will be before I ever make them? And if so, doesn’t this imply that I’m not free to do something else?

Worse, some people (correctly) accept the overwhelming physical evidence for determinism and then (incorrectly) become fatalists who say things like “what’s the point of carefully considering my actions if the choice I make is already determined” or “there’s no justice in holding criminals to account, since they weren’t ultimately responsible for their choices.”

I notice that in these kinds of conversations, people basically never adopt a bi-directional view of determinism. I think this kind of reasoning is flawed even in a universe with one-directional determinism, but bi-directionality gives us an intuition pump:

“What’s the point of carefully considering my actions if people in the future will be able to look around them and correctly deduce what my action was? Their knowledge already determines my action so I might as well not worry about it.”

or

“Everyone here should be held responsible for the crime that was committed yesterday, because it’s this present moment that determines what must have occurred in the past.”

In a bi-directional determinism, it’s equally correct to say that the future determines the past as it is to say that the past determines the future. And in that sense it’s equally correct to say that each person’s free will leads to consequences that ripple forwards and backwards in time. The universe is determined by the state of its contents, and we are its contents.

Ultimately, I think it’s important to step back and ask why we feel like we have free will in the first place. Nobody is really denying the presence of will, merely whether it’s truly “free.” And likewise, nobody is really denying the fact that our actions and decisions are in response to our observations and reasons. And finally, nobody is denying that our actions are a product of our thoughts and desires. The question of free will is better off dissolved than answered.

Utopian Determinism

As I’ve said before, I expect that one of the biggest differences between this world and Utopia is that Utopians are significantly more enlightened. But enlightenment is multifaceted and complex. It involves walking a careful line between acknowledging the ways in which we’re powerless and remembering that self-control is both possible and important. As the prayer goes:

“God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

courage to change the things I can,

and wisdom to know the difference.”

In Utopia a proper understanding of determinism helps build the wisdom to know what’s possible and what’s impossible. With it in hand Utopians can more clearly see the size of the quantum multiverse and appreciate the foundational principles of physics.