Remote Work

TLDR: Remote work is a huge win, when possible. Infrastructure and at-will employment help, but the big bottleneck is trust, and the resulting feedback loops around network effects.

Prerequisites: Nothing strict, but reading Opinions will help understand prediction markets

Why do so many employees of American companies live in the USA? The answer is obvious: because that’s where the work needs to be done! Whether you’re a plumber or a store manager, you need to be at a specific, physical location to do your job, and commuting from Mexico every day is a teensy-bit impractical.

But what about “knowledge work”? About 60% of the American labor force are knowledge workers — consulting, IT, administration, finance, design, media, legal, and similar professions have far less in the way of physical constraints tying them to a specific location. There are exceptions, of course, both in the sense of there being jobs that are tied to a specific location despite theoretically being knowledge work (e.g. scientists working with expensive equipment) and there being specific periods where physical presence is particularly important (e.g. architects getting a sense of a building site). But in general, most of these people could be living mainly in other places, and perhaps commuting into the USA when needed.

The cost of living in Mexico is about half of that of the USA. Other countries in similar time zones (Columbia, Ecuador, Nicaragua) can be even cheaper, and if one is free to live anywhere, it’s simple for someone to support a family of five in rural Vietnam or India, just on US minimum wage. Yes, there can be some additional drawbacks to living in a poorer place (e.g. less access to quality healthcare), but these can often be at least partly compensated for through travel.

The real reason it’s rare for knowledge workers to live in cheap places is complex, and involves a combination of bad infrastructure, cultural inertia, and bad policies.

Some of this changed during the pandemic. Companies that had previously insisted on in-office work suddenly became open to working from home and began exploring and adopting technologies that can make remote work comparably productive. Unfortunately, the pendulum now seems to be on the back-swing, and old cultures of in-office work are reasserting themselves, mostly for bad reasons. Remote work is decidedly not for every person or every job, but I believe careful analysis shows that it should more often be the default for intellectual occupations.

The Massive Benefits of Telecommuting

Before exploring the costs, drawbacks, and counter-pressures for remote work, let’s go through the reasons why it can be good.

Most obviously, people who work remotely usually have no commute. And even in cases where they use a co-working space, they usually don’t have to travel as far as they would for an in-office job.

I’ve been talking about on this blog since the beginning: time wasted in transit is comparable to lives lost. Reducing commuting time on work days by just 20 minutes for 1% of the world1 is about 800,000 years worth of time saved per year — 10,000 lifetimes.

In addition to burning life via wasting time, driving is also one of the leading causes of dangerous accidents. A reduction of that size would prevent ~2,500 deaths each year, and hundreds of thousands of injuries.2

And more mundanely, less need to drive also means less stress, needing fewer cars, spending less on roads, and less congestion during rush hour. In addition to the local costs, this would also reduce pollution and be generally more environmentally friendly.

At least as important as the ease of not having to travel, telecommuting allows workers the flexibility to arrange their work to match their needs (thereby often increasing productivity).

A typical example of this is that some people prefer being by themselves and being able to focus on a task without interruption, while others feel energized by an open workspace with lots of other workers visible. In a single office setting it’s hard to accommodate both preferences, but if each worker is doing their own thing, introverts can work from home by themselves, while extroverts can join co-working spaces optimized for having the right vibe.

Sometimes someone might have an infectious disease, such as a cold, but feel good enough to do work. Remote work allows that person to be productive where they otherwise couldn’t without risking coworker’s health.

Working from home is often vastly more convenient for caretakers, such as parents, who can often still accomplish a lot, but have highly specific needs. Women tend to benefit more from remote work arrangements than men, due to more often being in caretaking roles.

This increased flexibility is likewise invaluable for workers with disabilities or other special needs that extend beyond basic preferences. Getting to and from an office can be a huge obstacle for someone with mobility issues, as just one example.

A somewhat distinct form of flexibility is the way remote work allows employers to more easily deploy workers as needed, including to provide 24/7 support or to handle remote locations.

Beyond ease and flexibility, the primary benefit for workers is being able to live in more affordable places, where the cost of housing and other necessities is lower. (And save money on transportation costs.)

This benefit doesn’t just go to workers. Depending on negotiating power, employers can benefit from low costs-of-living by hiring workers who will happily work for lower wages.

Employers benefit from being able to cast a wider net when searching for talent, increasing competitiveness for job postings. Likewise, remote work means increased opportunities for workers, especially people in poorer communities.

Much like other trends in globalization, remote work is disproportionately good for talented, hard workers who live in less developed parts of the world. The flow of resources to these people and communities is egalitarian, and naturally reduces global inequality3 and extreme poverty.

Workers also just generally like being able to work remotely. Surveys clearly show satisfaction for remote or hybrid jobs being higher, on average. And thanks to the flexibility of remote work, this satisfaction can translate directly into increased company loyalty and reduced rates of turnover.

These benefits — reduced commute, flexibility, affordability, competition, fairness, and satisfaction — are huge when taken together. So why wouldn’t companies and workers be eager to go remote?

Infrastructure Investment

Thirty years ago, remote work was rare.4 Home internet, when people even had it, was primarily dial-up. Many people didn’t have home computers. And the idea of holding an important meeting in a chat room would’ve been a joke. Yes, there were a few early-adopters who worked mostly from home, such as authors or early computer programmers (including my father), but certainly nobody who needed real-time interaction could move to Thailand and expect to keep their job.

This changed, bit by bit, decade by decade, until the Covid pandemic caused many businesses to suddenly take stock and realize that it was now largely possible to work from anywhere in the world — in theory. Meetings could be handled on Zoom. Documents could be worked on together on Google Docs. And more specific needs could usually be handled through a variety of less well-known pieces of software.

But despite an abundance of technologies which make remote work possible, there are still several physical/technological barriers in practice. Most notable are speed and reliability of internet connections and the transportation of goods and people.

While high-speed internet is commonplace, it is not ubiquitous. In particular, there’s a catch-22 where poor places — whether they are rural areas of countries like the USA or India, or merely typical areas of countries like Namibia and Cuba — do not have the digital infrastructure to support remote workers, which means these communities have neither the resources nor demand for building high-speed connections necessary to attract them. And even when a place theoretically has a fiber-optic connection or other high-speed service, it often matters a lot whether that connection can be relied upon every day. Nigeria, for instance, has plenty of broadband internet availability, but suffers from an extremely unstable power grid that gives out over six times a week for an average of 12 hours each time.

Physical transportation infrastructure, whether it’s for freight or humans, also matters. Some knowledge work, such as biology, can sometimes be done remotely as long as there’s high-speed (and possibly refrigerated) shipping. More common is for remote workers to need to regularly fly or drive into a city to handle particularly important meetings or similar events. In both of these cases, lack of high-speed infrastructure can make all the difference. And beyond the necessities of the job, there’s a natural cost to being far away from civilization, and workers may not want to go remote if it means losing quick access to deliveries or hospitals.

Culture and Trust

But even though it’s important, infrastructure is not the main impediment to remote work. Rather, I think the biggest factor is cultural and psychological. Specifically, employers have a hard time trusting employees, and in-person environments are central to how humans build and maintain trust.

I got my first full-time job (making software) because two small businesses were sharing an office. I went in to apply to a job posting for one of them, and the guy I was interviewing with said, approximately: “I’m not going to hire you. You’re too weird. But my friend might be interested.” I then had my first interaction with my soon-to-be boss face-to-face (which I think was probably vital, since my résumé at the time was hot garbage). Other work that I’ve found has been similarly connected to the people I’ve spent time with face-to-face, and I think my experience there is not atypical. Not only do I know several people with similar stories of finding work through personal connections of various kinds, but I also know multiple business owners who actively try to hire people who are in their local communities and have personal relationships with people they know.

Looking to hire people through local connections seems fine, but why would it be someone’s preference, especially in domains like software, where remote work is easy? By casting a bigger net, and being willing to hire people from anywhere, I think it’s pretty straightforward to show higher expected productivity per dollar.

But the statistically expected productivity per dollar is actually not what most employers care most about. A star employee can potentially bring millions of dollars of value over their career, but the wrong person getting hired can ruin everything.5 Even productive employees can do immense damage to the company as a whole by breaking the law, alienating customers/clients/partners, or creating headaches for management. But the biggest risks usually come from the effects that bad employees can have on other workers and on company culture. Humans are social creatures and rely a lot on cues from peers as to how to behave; a single person visibly slacking off or criticizing the company’s direction can cascade into widespread inefficiency and chaos.

In other words, employers are naturally risk-averse when it comes to hiring, and so they select for workers they can trust (especially to maintain morale and culture), as well as those who seem like they’ll be productive. By hiring people who have an established reputation and who seem, face-to-face like they’ll be solid and productive, companies can better guard themselves against accidentally hiring someone who will do a lot of damage.

Similar dynamics are in play when companies decide who to promote. Workers who are physically present in an office have more opportunities to demonstrate that they are positively contributing to company culture, especially with their peers, while remote workers often have fewer such opportunities or are simply overlooked.

As long as companies are looking for these kinds of personal connections when hiring and promoting, network effects will dominate. Young professionals looking to get ahead in their careers will want to live in cities with lots of companies in their field, and work in offices where they can meet lots of coworkers. (Those with more established careers and bargaining power are more often remote.) And since ambitious professionals live in the cities, companies will naturally set up workplaces there.

These network effects form a self-reinforcing cycle. Since the most ambitious people will be urban, if someone lives in the countryside or wants to work remotely, this is a sign of lack of ambition, further pressuring those who want to signal ambition to live in the city.

Lock-In Policies

One might wonder why companies don’t just fire more people. Why not simply check who is talented, ambitious, and alignment with leadership, and then get rid of those who don’t measure up? There are several reasons. First, it’s not always obvious to management who is boosting and who is corroding company culture, both because “company culture” is vague and hard to measure, and also because disaffected workers usually try to hide their misalignment (so they don’t get fired!). Even when such firings happen, it’s often too late — influenced coworkers can continue to work against the leadership’s direction, and morale can drop as remaining workers fear that they might also be fired.

But often, the risks go deeper, and are tied to legal issues. Many places, such as Western Europe, Japan, Brazil, and Mexico have strong employee protection laws, but even in the USA, which is somewhat infamous for allowing employers to fire people “at-will,” has a variety of protections in place for workers, including anti-discrimination laws and the need to buy unemployment insurance. Additional restrictions come into play for fields with strong unions, such as education, journalism, government, entertainment, and healthcare. Even when an employer is justified in firing someone, the legal costs of fending off a wrongful-termination lawsuit can be intimidating.

These barriers are part of why businesses sometimes engage in “silent layoffs” — making employees lives worse and worse until they quit of their own initiative. (Another big reason is that many employment contracts involve employees losing severance pay or other benefits if they decide to quit, rather than being fired.) It’s hard to know for sure in any particular case, but part of what’s driving recent trends in demanding that employees return to the office is exactly this kind of stealthy downsizing.

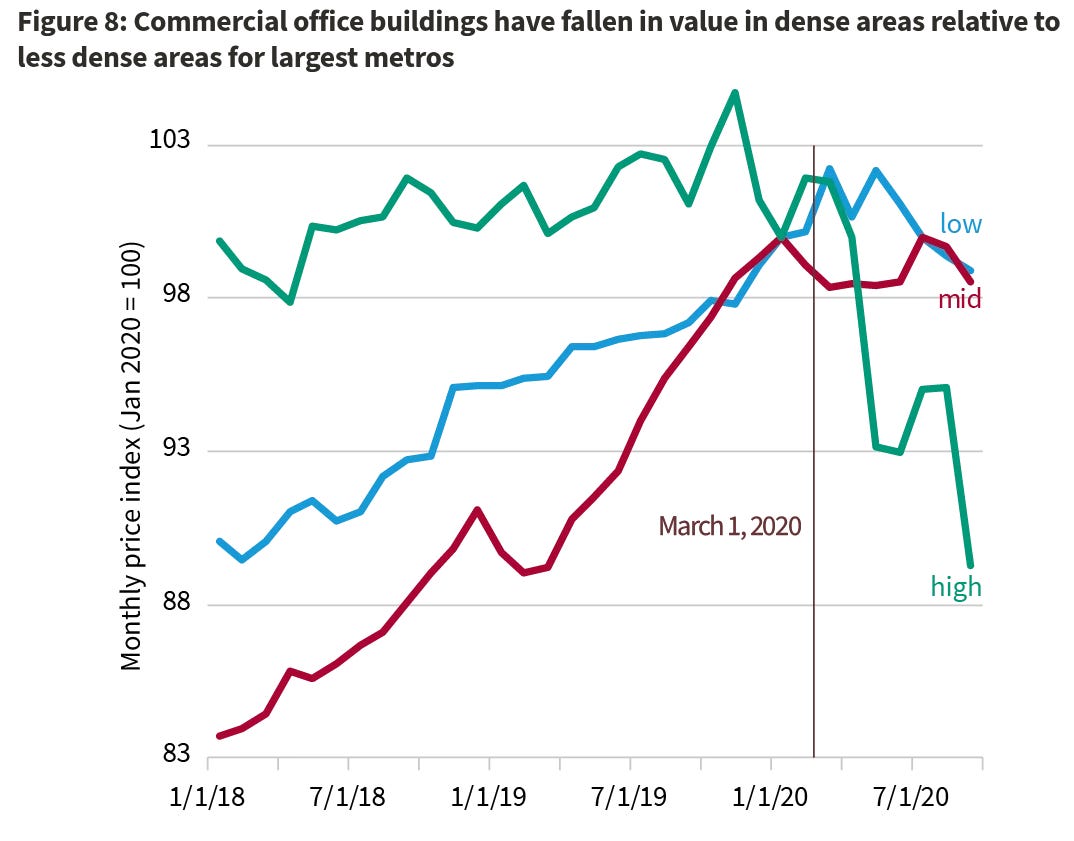

There are other legal policies at play in return-to-office mandates, as well. One major factor is that after Covid drove many businesses to go primarily remote (or hybrid), offices in many city centers plummeted in value.

As fewer people commuted into the urban core, businesses that depended on those workers are struggling, and city governments (which often rely heavily on property taxes) have seen sharp decreases in funds. Zoning laws and other regulations have meant it’s illegal to turn office space into apartments, and so cities have been using a mixture of tax incentives and fees to try to pressure companies to return to previous patterns of in-person work.

Utopian Remote Work

I think Utopia takes the need for high trust working environments very seriously. Low trust means having managers surveilling employees constantly, which is no fun for anyone, wastes resources, and imposes serious constraints, including reducing the feasibility of remote work. Part of how Utopia keeps trust high is cultural: people in Utopia put more emphasis on honor, honesty, and other virtues, and aren’t shy about holding each other to high standards. Another aspect is higher general levels of management competence6 and deliberate skill-building in communication. But the lion’s share of the problem is handled by three major pieces of infrastructure:

Prediction Markets

When a person — let’s call her Alice — is looking for employment, she typically contracts a third party7 to create two prediction markets:

“How long will Alice’s next full-time8 job last?”

“How highly will Alice’s next employer rate her after she leaves?”

These markets are used to signal to potential employers. But when a company — let’s call it McMart — is seriously considering hiring someone, it usually also creates a trio of more specific markets:

“Conditional on McMart hiring Alice for job X in the next Y months, how long will she work at McMart?”

“Conditional on …, will she leave on good terms?”

“Conditional on …, will she be at the center of any scandals?”

Gossip Brokers

While prediction markets are a good start, they’re not nearly detailed enough to tell an employer whether someone will be a good fit for their team. What would be nice is being able to interview people who know things about Alice’s character and professional history. In our world this is mostly done by providing references and work history on a résumé, but it’s often hard to follow up on these and there’s an obvious bias, since the applicant can choose whom to include.

Utopia solves this problem by having companies who are in the business of buying and selling gossip. These “gossip brokers” pay nontrivial money to interview people about the people they know, especially coworkers or professional colleagues.9 The brokers then compile dossiers on people, available for purchase by potential employers. By default, sources are anonymized, but can be revealed for a significant fee, which then gets split with the source as compensation for being exposed.

Gossip brokers are subject to a lot of scrutiny (by media, customers, and other brokers), and compete with each other on integrity.10 Nobody wants to buy lies!

It’s generally considered unhealthy for people to check their own dossiers, or at least to do so too frequently. Instead there’s a common cultural story that the best way to know what people are saying about you is to behave in a deliberate, consistent way, and trust that they’re saying you’re that person.

Talent Camps

Because face-to-face interaction is one of the best ways to build and maintain trust, in addition to the more market-based systems, Utopia has a plethora of venues where talented people (especially young people) are invited to come and network with each other and with scouts for potential employers.

These usually take the form of an explicitly programmed “camp” experience where a batch of people looking for work show up at a venue alongside a batch of scouts and managers for various companies. The program usually goes for about a week, and involves shared meals, collaborative exercises, and competitions between teams. Many such camps have only a few administrators, and rely on volunteer labor provided by the participants.

When a person is brought on to a Utopian team, by default they are expected to work in the same space as others on that team for at least a couple weeks as they get on-boarded and learn their role. This often involves staying in people’s guest-rooms or at hotels when the team they’re joining is remote, and can involve spending different weeks with different members of the team.

For knowledge work, the Utopian default is for workers to be able to locate themselves freely across the world. Such teams often go on retreats together for a week or two each year to maintain organizational cohesion. Despite the cost of flights and temporary living/working space, these teams usually save money compared to entirely in-person teams, due to not needing to pay for office space or housing in high-demand areas.

Due to increased prevalence of remote work, Utopia has more widespread access to high-speed infrastructure, and remote workers are seen as the lifeblood of many rural communities. Likewise, the hearts of cities are made less dense due to needing fewer offices. Utopian businesses generally have more ability to downsize at will, which leads to increased ability to hire without fear and less insanity around silent layoffs.

This is a significant underestimate for seriously increasing the number of remote workers across the globe. The fraction of the world population in just the USA is 4.2%. If we estimate that 60% of Americans are employed and 60% of those are knowledge workers, then reducing the commute of 2/3rds of knowledge workers in America by 10 minutes each way would give a reduction of the size I focus on in the essay.

Wikipedia says the USA has 6.9 fatalities per billion kilometers traveled by automobile. US roads are more dangerous than in Canada and Western Europe, but less dangerous than Mexico and Asia.

Let’s say that the average speed for a commute is 50 km/h. This means 800,000 years of driving is equal to 3.5e11 km. 3.5e11 * 6.9e-9 = 2,415 fatalities.

It’s not really possible to estimate how many injuries are associated with driving because what constitutes “an injury” is too vague. I think reasonable notions of injury could range from 10x as many injuries as fatalities to 200x as many injuries as fatalities.

Remote work reduces global inequality by bringing the median wealth of countries closer together. Arguably it can also increase inequality if the benefits on the corporate side particularly accrue to wealthy owners. We’ve seen some of this play out with the rise of global manufacturing and digital economics, and I do not have a strong stance on whether the benefit to the world’s poor from remote work is stronger or weaker than the benefit to the 99.9th percentile elite, from the perspective of any particular inequality index.

It’s hard to say how many people “worked remotely” in 1995, compared to people who worked out of their homes in a job that does not match our current notion of “remote work.” An example of the latter might be a daycare that’s set up in a residence — it’s “working from home” but still extremely location-dependent. The US Census Bureau indicates about 5 million home workers who were not self employed. An academic at the University of Buffalo, in discussing difficulties in estimating trends in telecommuting, says that LINK Resources estimated 7.6 million “part- and full-time telecommuters.” Given that the workforce at the time was about 130 million people, I think it’s fair to say that between 1% and 6% of workers were meaningfully remote in 1995, depending on how you count.

Interestingly, while startups and other small companies are more at risk in some ways from hiring the wrong employee (since that employee will be a large fraction of the company), small companies are usually more open to remote work, since they’re naturally more nimble and oriented around flexibility. Needing to frequently onboard a lot of junior workers, by contrast, makes larger corporations gravitate towards in-office work, despite the fact that each new hire is less of a risk.

I think it’s a little unfair for me to say “this is less of a problem in Utopia because of increased competence” but also… it can be true! Our world is less meritocratic than Utopia for a variety of reasons, and I may write directly about meritocracy in the future. But even things like improved public health can have massive spillover effects. Part of the project of Utopia is generating these kinds of virtuous-cycle externalities, such that nearly everything ends up better for a host of reasons.

The market creator, who specializes in these kinds of markets, prohibits Alice and her manager/employer from trading. Coworkers and other “insiders” are still allowed to make public bets, however, as the markets are primarily meant to surface information, not be fair investment opportunities for outsiders.

The specific language is actually usually something more like “primary, indefinite-duration job.” This is meant to rule out side-gigs or temporary work, but meant to include less-than-full-time work if Alice isn’t working somewhere else.

There are also gossip brokers for relationships who interview people about their exes, but they’re not particularly common. Exes are usually not particularly trustworthy, and individuals are generally less interested in paying large amounts of money to get a very noisy signal about who’s a good romantic partner.

Gossip Brokers are also subject to the same legal restrictions around surveillance and privacy as any business.