Anthropic Reasoning

TLDR: You can be multiply-instantiated, with no truth to the question of which is the real you. Beliefs are not anticipations. It still makes sense to anticipate being different instances, but how you should anticipate depends on your values.

Prerequisites: Decision Theory

I remember, when I was, like Alice in Through the Looking-Glass, young enough to wonder when I looked in the mirror whether I was seeing another universe with a different child who just happened to be doing exactly the same things I was. Did that kid have the same uncertainty as me? Or perhaps the people in the mirror universe were deliberately mimicking us as part of some elaborate trick?

Long before we learn anything about light waves or the principle of parsimony, we form intuitions about mirrors and people. But as we explored in my essay on decision theory, these folk-theories are often subtly flawed in ways that only really become apparent outside of familiar contexts.

In this essay I want to talk about “anthropic reasoning” — a branch of philosophy that explores what it means when there are multiple versions of you, and how that should shape your beliefs and choices. You may think this is a bizarre notion; there’s exactly one of you! But as we saw in the previous essay, clinging too tightly to folk intuitions about identity can lead to self-defeating behavior. Your decisions are naturally reflected in many places, such as in your past and future selves, and in the actions of similar people. These points of reflection aren’t just relevant for decision making; they offer a window into the nature of self and our place in the universe.

The Duplicator

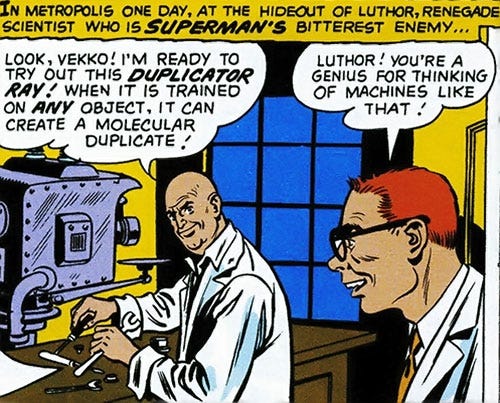

We’ll talk about ways in which anthropics applies to everyday life a bit later on, but I want to dive into the subject by first imagining a potential technology that doesn’t yet exist: the duplicator. Duplicators are machines that scan whatever is put into them at a very deep level, then build a copy of that input that’s indistinguishable, even at the cellular level. For example, I could put a strawberry in the duplicator and two strawberries would come out that would appear identical, even under a microscope. The specifics of how a duplicator might work goes beyond the focus of this essay, but we might imagine nano-scale machines crawling through the subject with atomic probes or something.1 The point is that even for something as complicated as flesh, the duplicator has enough resolution to capture and reproduce all the relevant details.

And by “flesh” I mean you. You’re entering the duplicator. In you go. Don’t worry. It’s perfectly harmless.

Inside the duplicator is a dark chamber, and in order to keep you from moving around during scanning, it administers a sedative gas that knocks you out. When you wake up, you’re still in the machine. You feel a little strange… maybe that’s an after-effect of the sedative. But are you actually the original?

Human beings evolved to be natural dualists. Across cultures, and among children, we see beliefs and intuitions that suggest each person has a soul, which is unique to them, and is distinct from their body, including by potentially continuing on after the body has died. These intuitions emerge from a brain that’s wired to sharply distinguish people from objects and think about them very differently. When someone’s body changes, we assume that they’re still the same person, underneath. But this naive perspective doesn’t hold up well in the light of modern neuroscience, which shows that we can physically locate memories, skills, beliefs, and intuitions in the structures of the brain.

The copy of you that the duplicator creates will have a brain with identical structures, and thus have all of these same memories, skills, beliefs, and intuitions. That body will be a person who will start out believing with equal conviction they are the original you. When both people leave the machine, they can see who came out of which chamber, and thus who is the copy and who is the original.

Wei Dai’s Paradox

So let’s suppose you wake up, having memories of having gone into the duplicator. What do you anticipate seeing when you come out? What should you anticipate? Should you expect to see that you’re the original? Should you expect to be the copy? You certainly shouldn’t expect to somehow see that you’re both, at least in the normal sense of “see,” since neither version of you will get that experience.

Savvy readers may be inclined to say “Just as with the flip of a coin, I don’t put all my anticipation on either outcome, but instead assign 50% of my prediction to each.” Indeed, if each of the people on the way out of the machine are forced to bet on whether they’ll see that they’re the copy, 1:1 odds is the breakpoint for whether those bets are profitable in total.

Now suppose the plan is for the copy (and only the copy) to go back into the machine, producing a double-copy. Presumably those versions also believe there’s a 50% chance of being the double-copy prior to leaving the machine and finding out. A simple multiplication indicates 50% likelihood on being the original after the machine has activated twice, 25% on being the copy, and 25% on being the double-copy.

Does that sound right? Do you, prior to getting any information, expect there will be a 25% chance of being the double copy at the end of the day, a 25% chance of being the single-copy, and a 50% chance of being the original? Many people think this doesn’t make sense! Using the exact same logic as we used to get the 1:1 odds from before, we might argue that at the end of the day there will be three bodies, and thus there’s a 1/3 probability attached to each of them. Indeed, this matches the betting logic; 2:1 are the breakpoint odds for total profitability if each of your end-of-day instances bet on being the original.

But a 1/3 chance also gives a weird result. Presumably it indicates a 2/3 chance, before leaving the machine the first time, of seeing that you’re the copy! That can’t be right, can it??

And what if, after the first duplication, another copy of the original is created in secret, but dies quickly inside the machine. Should we somehow anticipate, after the copy has died, that there’s a chance you’re now dead?

Indeed, there are many possible responses here, and I’ve seen brilliant people intensely divided by this sort of scissor statement. But I think one of the best is to notice the confusion, and ask whether we’re being steered wrong by some evolved intuition.

If we frame things purely in terms of offering bets to people in specific situations, there are clear, objective answers about what odds are profitable overall. And note that if we frame the question in terms of what fraction of selves have which memories, it’s also easy and unambiguous; 1/2 of your instances will experience being the copy when there are two of you, and 2/3 will remember having been the copy when there are three. So where is all this confusion coming from?

Incoherent Belief

If all we have are thoughts about ratios and bets, Wei Dai’s paradox dissolves. But we, as human beings, also have questions like “what do I anticipate experiencing” and “what do I believe about the world” that hang around even once the more unambiguous stuff is known. Anticipations and beliefs are useful, but we need to think carefully about how to shepherd them into alignment with anthropics, rather than assume our natural intuitions will serve us well.

Let’s start with beliefs. Beliefs are like maps of the world, telling us what’s out there and how things will work, so that we can chart a course towards what we want. When the map lines up with the territory we say that it’s “true.”

I claim that “I will be either the original or the copy after going through the duplicator” should either be seen as false, or perhaps as so confused it’s not even worth calling “false.” It presumes that there’s some property in the world (akin to a soul) that can be used to identify which of the future people is the true continuation of the past self. But there is no objective test that will settle this question! Each future self will remember being the past self going into the duplicator, and by the assumption of having a duplicator, they’ll be structurally identical. So why does our intuition offer “Will I be the original or the copy?” as a sensible question?

Imagine tossing a coin: you can foresee two hypothetical futures. Only one future is the factual outcome that will occur, while the other is counterfactual.2 I think the intuition that “I will either be in the heads future or the tails future after flipping the coin” is correct and useful. When we look back, after seeing the outcome of the flip, we can also say that our past self was going to become this future self, and just didn’t know it back then.

In Wei Dai’s paradox there’s a similar feeling when we imagine being one of the future selves who remembers being the double copy or whatever. When we put ourselves in any particular shoes, there’s a temptation to re-apply the same mental motion and say “I was always going to be the double copy, and just didn’t know it back then.”3

It might make sense to say there’s something here. After all, it seems like claiming “I am both the copy and the original” like some kind of enlightened centrist and calling it a day would be leaving something out. Those different future people are going to encounter different situations, and need to prepare for being in one situation or another. For instance, if the duplicate is doomed to age rapidly compared to the original, it might make sense to start preparing for rapid aging in advance knowing who’s the original and who’s the duplicate. Having a subjective feeling of “I have a 50% of being the short-lived duplicate” might be a good way to reflect this need to prepare. Nevertheless, it doesn’t make sense to say this is a fact to be believed; the real fact is that all but one of your future instances are going to find out that they’re short-lived, and there’s no objective property, prior to being duplicated, that can possibly tell you which one of those future selves you “really are.”

Brace Yourself

But even if there’s no fact about whether you’re going to be the copy or the original, it still makes sense to have anticipations about which futures you might experience, each with different weights. Anticipations are useful! They’re almost like an action. If I anticipate a tiger, my body starts pumping adrenaline so I can spring into motion much quicker than if I anticipate safety, but also I incur some stress and distraction if there’s no tiger there. In this way, an anticipation is akin to making a bet.

If you anticipate a high chance of winding up as the original and a high chance for being the copy, both of your future selves will be relatively unsurprised when they see who they are. Conversely, a person who’s absolutely certain they’re going to experience being the original will have one of their future selves say “I knew it.” Meanwhile, the other person coming out of the machine is having a panic attack from having their worldview shattered.

Since anticipations are like bets, what you should anticipate depends on both your view of what’s true, and also what you care about. If you want to avoid having any future instance of yourself break down in a worldview shattering crisis, you shouldn’t put all your anticipatory weight on being the original. But conversely, if you want to avoid having your original self surprised at all, you definitely should put 100% on expecting to be the original!

In mundane circumstances, you should probably just anticipate experiences solely according to what you believe is true, since being ready for the real future is generally good, regardless of your values.4 But when we get into exotic situations involving duplicators and so on, it seems right to me to start thinking about anticipation more as a question of “how do I want my instances to behave.”

If you’re looking to minimize total surprise, the right move is to evenly divide your anticipation between being the original and being the copy before stepping into the duplicator… unless you can close your eyes! Using the power of eyelids you can simply expect darkness and be unsurprised when you see nothing. Life hack!

This is a little bit of a joke, but also somewhat serious. Minimizing total surprise is best accomplished by not duplicating yourself at all, and generally gathering no information.

From this perspective we can see the 1/3 position on Wei Dai’s paradox as corresponding to a pretty different situation than the one presented. If one can blind oneself until after all duplicating is done, anticipating each label with 1/3 probability minimizes the overall surprise of your instances. But if you are forced to see which label you have half-way, you’ll necessarily do worse with than a strategy that anticipates 50% each time you duplicate.5

Sleeping Beauty

The most famous thought experiment in anthropics is “Sleeping Beauty.” I’ll be presenting my version instead of the standard one, since I think mine captures intuition better.

In the rom-com film 50 First Dates, Drew Barrymore’s character suffers from anterograde amnesia, forgetting her experiences at the end of each day when she goes to sleep and waking up each morning believing it to be the Sunday, October 13 — the day when she got into the car accident that gave her the condition — regardless of how much time has actually passed. While oversimplified for the sake of the story, anterograde amnesia is a real syndrome, and it’s possible to wind up in a similar situation.6

Suppose that you wake up, and before looking at the calendar, you remember that today’s the day you’re scheduled to have a risky brain surgery that the doctors claim has a 1% chance of inflicting this condition. What’s the probability that you already went through the operation many weeks ago and currently have anterograde amnesia?

Again, I encourage being careful to notice potential confusion. Attaching a probability to a statement is useful for making bets and acting under uncertainty, but there are multiple kinds of bets that we should be careful to distinguish between, even if they anchor to the same proposition (ie “I have anterograde amnesia”).

One kind of bet is a single-opportunity bet — one where you will only ever have one opportunity to make that bet in your life. I claim that 1% is a good credence to have here. You almost certainly don’t have amnesia, but you shouldn’t be absolutely sure.

Another kind of bet is one that you’ll encounter each morning where you remember it being the day of the surgery. In the rare case you get amnesia, you’ll be asked to make this bet again and again and again, and your answers will be importantly correlated — if you say “1%” you might lose a lot of money over and over.

While our intuition might say that “I have amnesia” is a statement of fact, rather than value, the odds we should accept for a bet on that statement depend on what we care about. Likewise, the correct experience to anticipate also depends on your values. If you’re okay with a 1% chance of condemning yourself to a big surprise every morning, by all means anticipate not having amnesia. But if you would rather have a 99% chance of incurring the one-time shock of not having amnesia in return for hedging against that 1% terrible outcome, you should anticipate that you already have amnesia even without any evidence.

This is a pretty strange result! It says that one kind of person, upon learning that they may have a tiny chance of incurring brain damage, should become almost-certain that they’re already brain-damaged, at least when considering their anticipations and behavior (rather than abstract “beliefs”). I’ll describe this kind of person as “Spread.” In the extremes (which we’ll get into more in a moment), even a slight bump on the head might send a Spread into an intense conviction that they’re about to see evidence that they’re in a weird, unfamiliar world. Meanwhile, another kind of person, whom I’ll call “Based,” might share none of that conviction, and see no reason to anticipate anything other than the objective base-rate. And importantly, our reasoning says we’re not allowed to say either of these people is wrong (any more than we can say people with generally different values are wrong). Both the Spread and the Based should bet the same way if they know it’s a single-opportunity bet, such as when it’s about someone besides themselves, and both will have roughly the same explicit beliefs.

In a naive sense, Spread people are exploitable when they don’t have retrograde amnesia in exchange for being hard to exploit when they do. A Spread person will intuit a high chance of having amnesia “against the odds,” since they care about not being huge fools over and over again if they actually do have the condition. Conversely, Based people are extremely vulnerable in the off-chance that they do get amnesia in return for being hard to exploit in the majority of cases where they don’t. Less naively, both kinds of people will wisely stay away from bets where their betting partner knows more than they do, and may update on attempted bets as a strong signal about which world they’re in, making them less exploitable than their intuitive anticipations would indicate.

The Simulation Big World Hypothesis

Are you Spread or Based? My guess is that your revealed preferences put you in between. Or rather, I think you’re off to the side rather than being a strict blend of their perspectives. Both stances lead, in the extremes, to weird results and somewhat insane behavior, I think. Neither stance fully captures what we care about.

Let’s examine this by turning our attention to a place where Spread people seem particularly crazy to me: worlds with huge numbers of instances in powerless situations.

A common example of this scenario is “the simulation hypothesis,” which supposes that in the future, large numbers of computers might be built which run simulations of ancestral humans on 2025 Earth, akin to an extremely sophisticated video-game. If this happens, we might suppose that there will be billions of these simulations, each with billons of people contemplating whether they’re a simulation. Are you a simulation? Even if you think there’s an extremely tiny (i.e. <0.000001%) chance of this happening, the Spread position says we should anticipate being a simulation, since they outnumber real ancestors in expectation by more than a thousand-to-one. Spread people argue that anticipating being in a simulation protects the majority of you from being shocked by your digital nature.

There are a lot of things one can quibble with in this setup, but I want to argue that even if we take those numbers as true, it does not follow that we should anticipate being simulated. Notably, we might care a lot more about the instances of ourselves that live in the true 2025 Earth! The whole future depends on those “ancestors” behaving in a way that aligns with their situation, while the benefits for simulated selves anticipating that they’re in a simulation seem small. Perhaps a simulated self has an increased chance of escaping the simulation if they anticipate they’re in one, but ancestors go marginally more crazy with the same anticipation. Having a significant number of “ancestors” going crazy seems pretty bad, even if you only care about simulated existence, since it reduces the likelihood those simulations coming into existence in a good future.

Note that this is more of a rejection of being (purely) Spread, rather than of being Based per se. The Based perspective might say something like “I anticipate being a simulation with <0.000001% probability because that’s how an outside observer would bet, given the evidence.” But imagine if, instead, you have evidence that makes you 99% confident that those billions of simulations will exist (or already exist) — both the Spread and Based positions say you must now anticipate being a simulation. But the real world might still matter to you much more than any simulated world does! I hold that it’s plausibly sane and rational for such people to ignore the imperative to minimize total surprise and instead continue to anticipate that they’re not in a simulation, even when most of their instances definitely are.7

Again, my claim is not one about what is true or what should be believed, but rather of what should be anticipated. I think Spread, Based, and other smart people should be able to agree about “objective” probabilities on beliefs, such as about whether simulations exist (in some timeless sense). And if we condition on many copies existing, I think the only belief that can be true is that each of those instances of you are equally you. Different people are simply allowed to assign weights to their various instances in the context of specific bets or the need to anticipate experiences, depending on their values.

Utopian Anthropic Reasoning

Much, much more could be said on the topic of anthropic reasoning. In the course of writing this essay I had many drafts that had lengthy engagements with the writings of other philosophers in the field (many of whom I very much respect) and an exploration of all the various thought experiments that I’ve grappled with in coming to my positions. If you’re curious for more, I’ll put some of that in a footnote.8

But in a field that is both struggling to pry people away from their folk intuitions about identity and selfhood, and where there’s also no consensus among experts, I think it’s vital to keep to a clear and simple story, rather than getting mired in the writings of previous thinkers. So here’s the idea, once again, for reference:

People, including you, are patterns that can be instantiated in multiple times and places. There is no fact of the matter as to which instance of the pattern you “really are” — you are reflected in each of them. Different versions will split off as they have different experiences. Anticipating those experiences helps you prepare your instances, but which anticipations are best depends on which instances you care about, and your broader values. Human beings do not have values that can be easily summarized by things like “minimize total surprise” — it is probably better to summarize your values with reference to things like “I care about being psychologically prepared for simple/common situations where I have opportunity to help those I care about (including myself).”

In Utopia, I believe stories like this one are a helpful bridge away from the flawed world model that children naturally develop, and towards a more broad, encompassing view of reality. Religion in Utopia is flavored less by myths of miracles performed by historical figures, and more by contemplating the vastness of reality and the way our selfhoods are interlinked in subtle ways. Utopians use these ideas to stay grounded in the face of weird cosmologies and technologies, and foster cooperation between strangers.

More realistically, we can consider artificial people who can be copied endlessly from some fixed, digital storage.

Quantum effects muddy the waters here, but not to any useful effect. Let’s ignore them for the moment. Or, if it’s too distracting, consider speculating on the billionth digit of the binary representation of pi instead of actually flipping a coin.

This mistake resembles the confused question of “why am I me and not you?” that supposes that there’s a lottery of which souls are attached to which bodies, and that there’s a fact in the world that could’ve been a different way. But of course, if “I were you” then I’d have exactly the same beliefs and perspectives and values by assumption, leading to a world that’s 100% identical.

I know of two potential exceptions to this prescription. First, as Duncan Sabien once wrote, Murphy’s Law is more true the less you believe in it, and the more you believe in it the less true it becomes. Because Murphy is inconvenient, it can be worth believing that things will naturally go wrong so that you prepare adequately, even though that prep might mean things don’t naturally go wrong. Second, I find it’s nice to foster “irrationally” low expectations of movies, food, and other entertainment, so that my experience is consistently one of being pleasantly surprised. Both of these are weird human mental tricks that I believe a superior mind wouldn’t need, but they’re still useful.

Because you have multiple selves, each getting an outcome, the total Brier score is the total squared error across your instances. Let’s say you give 1:1:1 odds to each “outcome” and manage to stay blinded until after duplicating is done:

BlindScore(1:1:1) = [(2/3)² + (1/3)² + (1/3)²] + [(2/3)² + (1/3)² + (1/3)²] + [(2/3)² + (1/3)² + (1/3)²]

= 3 [4/9 + 1/9 + 1/9] = 2

BlindScore(2:1:1) = [(1/2)² + (1/4)² + (1/4)²] + [(1/2)² + (3/4)² + (1/4)²] + [(1/2)² + (1/4)² + (3/4)²]

= [4/16 + 1/16 + 1/16] + 2 [4/16 + 9/16 + 1/16] = 3/8 + 14/8 = 17/8

Lower is better, so if you can stay blinded, you should bet 1/3 on each. In the unblinded case, however, we accumulate squared error both from the first duplication and the second duplication. Let’s start with the strategy that anticipates being the duplicate on the first copying, in line with the “1/3 total measure” story:

Score(1:2, 1:1) = [(2/3)² + (2/3)²] + [(1/3)² + (1/3)²] + [(1/2)² + (1/2)²] + [(1/2)² + (1/2)²]

= 8/9 + 2/9 + 1/2 + 1/2 = 19/9

Score(1:1, 1:1) = [(1/2)² + (1/2)²] + [(1/2)² + (1/2)²] + [(1/2)² + (1/2)²] + [(1/2)² + (1/2)²]

= 1/2 + 1/2 + 1/2 + 1/2 = 2

Again, lower is better, so if you can’t stay blinded you should anticipate equal probability each time to minimize the total error across all instances.

One person I talked to about this thought experiment insisted that he’d be able to tell the difference between having amnesia and not having amnesia. Fine. Whatever. I claim that fighting the thought experiment might get you out of having to have an answer to this particular question, but it also don’t bring you any closer to enlightenment.

Those who are familiar with Newcomb’s problem can use this same reasoning to justify anticipating that they’re a simulation in Omega’s mind, since it’s that simulated version that has causal power. I don’t strongly endorse this position, but it’s nice to see that the logic of anticipate-being-the-selves-you-care-about doesn’t mess with good decision theory.

Likewise, this same argument can be used to handle the possibility of Boltzmann brains. Regardless of how many disembodied copies of you there are floating out in space, it seems reasonable to only really care about the instance(s) on Earth(s).

Responding in More Depth to Prior Work

The whole field of anthropic reasoning mainly traces back to Brandon Carter, who introduced the term at a cosmology symposium in 1973. The issue at hand was that we see a universe that seems to be “tuned” in various ways to be able to support life. For example, the distance from Earth to Sol is in a very small band where liquid water is common on the surface. In a more extreme example, the cosmological constant (which determines how fast space expands) appears to be fine-tuned to roughly 1 part in 10^120. If it were larger, the universe would’ve expanded too quickly for galaxies to form. If it were smaller the universe would’ve collapsed back in on itself long ago. How might we explain this tuning, if not by reference to God?

Carter argued that it was quite simple: suppose there are different universes (or parts of some great big universe) with different values for these parameters. (This is easy to imagine in the case of planetary distance to the star, but requires more of a stretch for the cosmological constant.) In places where the parameter is incompatible with life, there are no observers. Because we are observers, we can conclude a priori that the parameters support life. This fine-tuning is evidence of a very large universe where life is rare, but we shouldn’t use our own existence as evidence for how rare life is, since that would bake in an obvious observer-selection bias.

But things aren’t quite so simple. Suppose that in some parts of the universe the parameters are just barely right, leading to a low probability and/or low frequency of life, while in other places sentient life is common, thanks to the parameters being well tuned. Should we expect, even before looking around us, to find ourselves in a densely populated part of the universe or in one of these barely-habitable zones?

Be careful not to let the field’s fundamental confusion bite you! Many people will read that paragraph and nod along with an unspoken presumption that the reasoner is only in one place or the other, and there is a fact of the matter where they are. But if you truly know nothing about yourself or your place in the world, you are reflected in all bodies that are ignorant, whether they’re in lush valleys or desolate wastelands. There is no truth about “where you will find yourself.” Your futures will find themselves in various places.

The question, however, is what we should expect, and that has an answer once we’re clear on what we care about. Expecting to be in a populated place will lead fewer of your futures to be disoriented, and is thus a generally good bet. And for any particular feature of the world, we should probably expect to see that feature in proportion to how many of ourselves are about to see it.

In his 2002 seminal book on the topic, Anthropic Bias, Nick Bostrom presented two competing schools of thought on anthropics: SSA and SIA (technically “SSA+SIA” but that’s confusing so I’ll just refer to it as “SIA”). (And actually he presented several competing perspectives, but these are the ones that have stood out in my intellectual circles.)

The Self-Sampling Assumption (SSA) — “All else equal, you should reason as if you were selected (uniformly at random) from the set of actually existent observers (past, present, or future) in your reference class.”

The Self-Indication Assumption (SIA) — “All else equal, you should reason as if you were selected (uniformly at random) from the set of all possible observers.”

These are not the only possible perspectives. Indeed, my perspective is neither, since I reject the notion of “reason as if you were selected (uniformly at random)” But these are the two most famous schools.

Joe Carlsmith, one of my favorite philosophers in the field, wrote a compelling takedown of the SSA perspective, and suggests that SIA is a superior alternative. For example, while SSA naturally picks the perhaps-appealing stance on Sleeping Beauty that waking up offers no evidence about whether you have amnesia, it gives rise to weird ideas like the Doomsday Argument:

While we can’t see how many people there will be in the future, we can be pretty certain how many people have been born so far (at least on Earth) — around 100 billion. Suppose that there was about to be some apocalypse in the next century that stops anyone from being born (such as by killing everyone), such that in total ~200 billion people come to ever exist. The chance of being drawn somewhere in the middle of the sequence is pretty reasonable. But suppose instead that humanity goes on to populate the universe such that there end up being some gargantuan number of future people, like 10^40. It would be extremely unlikely for you to exist on Old Earth, the birthplace of civilization! Thus we can conclude an apocalypse is imminent and likely inescapable.

If you don’t want to believe in Doomsday, but still want to believe in SSA, you might come to believe that almost all future people are simulations of Old Earth. That way you can be typical again, without needing there to be an apocalypse.

But it turns out this line of reasoning leads to other weird arguments that are harder to dismiss using Simulation Theory, such as:

Adam and Eve are walking around in Eden when they encounter a river that they’d like to cross. Adam makes a solemn vow to himself: “If this river immediately changes course so that we can cross to the other side, I will never sire any sons and the species will end with me. If not, I will be fruitful and multiply, filling the future with offspring.” While the chances of the river suddenly changing course are low, the chances of literally being Adam in the timeline where 10^40 come to exist is much lower. The river thus obeys his will in a miracle of probability, and Adam never has kids, making the whole experience much more likely (probability of being Adam = 50%).

This is… completely nuts. For starters, this line of reasoning only works if Adam isn’t sterile, but SSA also says that it’s almost 100% likely that he is. Whoops! But also, do you really think Adam effectively has telekinesis, by way of having power over how many people can be born?

SIA offers a different line of reasoning:

If there are two possible timelines: one with an apocalypse such that only 200 billion people ever exist, and one where 10^40 people come to exist, it is extremely likely on priors that you will find yourself in the universe with the huge number of people. But then, seeing that you’re one of the first ~100 billion will also be a huge shock. These unlikelihoods exactly cancel out such that you will wind up totally ignorant (from this line of reasoning) which timeline you’re in.

But SIA has its own flaws, most notably a thought experiment cooked up by Bostrom, under the title of The Presumptuous Philosopher:

There are two cosmological theories, T1 and T2, both of which posit a finite world. According to T1, there are a trillion trillion observers. According to T2, there are a trillion trillion trillion observers. The (non-anthropic) empirical evidence is currently indifferent between these theories, and the scientists are preparing to run a cheap experiment that will settle the question. However, a philosopher who accepts SIA argues that this experiment is not necessary, since T2 is a trillion times more likely to be correct.

Note the distinction here with the Spread stance, which holds that it is preferable to anticipate as though randomly selected from the set of all possible instances. Both SIA and Spread people will intuitively feel as though that they live in the T2 universe even if scientists say the evidence favors T1 at a billion-to-one odds, but SIA says “I believe T2 is probably true, despite the evidence” where Spread says “I abstractly believe T1 is probably true, but I care about the set of T2 instances more because there are more of them, and will thus act in some ways as though T2 is true.” (Again, I don’t think Spread values actually match human values very well!)

Indeed, I claim that this distinction is vital when moving to considering infinite universes. On our best cosmological accounts, our universe appears to be potentially infinite in many different ways: endless space, cosmological fine-tuning, and quantum multiverses, if not all-out modal realism. The same mathematics that lets SIA be ignorant over how many people exist when conditioning on a finite universe, demands that (if possible) we believe with 100% certainty that we live in an infinite universe with an infinite number of copies of ourselves. Despite this perhaps agreeing with the evidence, it seems like a very bad epistemological move. Are you saying that a priori all reasonable people must be fully convinced of the infinity, such that no amount of evidence could sway them? Are you saying that learning you’re in an infinite universe shouldn’t be at all surprising? (SSA has the opposite problem: it demands a finite number of observers in the universe, a priori rejecting our best cosmologies (and instead putting a lot of weight on solipsism), which seems even worse.)

My perspective says that while we can certainly reject the notion that we live in any universe that has no instances of ourselves, beyond that the quantity of instances has no bearing on which of those universes is real. The reality of a universe — or more mundanely, the truth of a belief — has no relationship with who is considering that belief. Noticing that you exist, regardless of your place in the historical order, should not be a surprise that counteracts some strong prior belief about how the universe must be.

Instead, in order to be able to coherently make decisions, bets, and anticipate outcomes, we must find a way to weight possibilities, including the possibility that you’re infinite, according to our values. Some values (ie pure Spread) will put infinite weight on those possibilities, and thus pragmatically neglect finite universes not because they are impossible, but because they are relatively unimportant. But I suspect that actual humans have something more like bounded utilities, and even the possibility of infinite instances of yourself being wrong about something doesn’t feel infinitely bad.

(This stance also offers an interesting interpretation of the Born Rule. Just like we care about Earth because it’s where we were born/evolved, we care about a section of the multiverse that supports histories like ours in a fairly simple way. And, this form of caring causes us to inherently anticipate that our futures will resolve in a way that’s similar to those histories. In other words, quantum wavefunctions may relate to “probabilities” by way of the square of the amplitude not because of a physical law, but because that’s what we care about. I don’t strongly support this interpretation, and am still confused by the Born Rule, but it’s a clever “solution.”)

Joe Carlsmith is aware of my school of anthropic reasoning, and dedicates an entire essay to addressing it:

… What’s the use of talking about credences, if we’re not talking about betting? What are credences, even, if not “the things you bet with”? Indeed, for some people, the question of “which anthropic theory will get me the most utility when applied” will seem the only question worth asking in this context, and they will have developed their own views about anthropics centrally with this consideration in mind. Why, then, aren’t I putting it front and center?

Basically, because questions about betting in anthropics get gnarly really fast.

Carlsmith then goes on to demonstrate the “gnarly” quality of this stance by considering how you might be inclined to use Spread logic to conclude that the probability of amnesia in Sleeping Beauty is higher than 1%, but if you do, then if you also use decision theory to make bets based on how many instances of yourself those actions affect, you wind up with a weird double-Spread position.

… in this case, your betting behavior doesn’t align with your credences. Is that surprising? Sort of. But in general, if you’re going to take a bet different numbers of times conditional on outcome vs. another, the relationship between the odds you’ll accept and your true credences gets much more complicated than usual. …

Indeed, I simply bite this bullet, if it even is a bullet. I think it is common for optimal betting strategy to diverge from credences, such as whenever someone buys insurance. There’s no escaping this.

A bit later in the essay, we get this paragraph, which I really like:

More generally, it doesn’t feel to me like the type of questions I end up asking, when I think about anthropics, are centrally about betting. Suppose I am wondering “is there an X-type multiverse?” or “are there a zillion zillion copies of me somewhere in the universe?”. I feel like I’m just asking a question about what’s true, about what kind of world I’m living in — and I’m trying to use anthropics as a guide in figuring it out. I don’t feel like I’m asking, centrally, “what kinds of scenarios would make my choices now have the highest stakes?”, or “what would a version of myself behind some veil of ignorance have pre-committed to believing/acting-like-I-believe?”, or something like that. Those are (or, might be) important questions too. But sometimes you’re just, as it were, curious about the truth. And more generally, in many cases, you can’t actually decide how to bet until you have some picture of the truth. That is: anthropics, naively construed, purports to offer you some sort of evidence about the actual world (that’s what makes it so presumptuous). Does our place in history suggest that we’ll never make it to the stars? Does the fact that we exist mean that there are probably lots of simulations of us? Can we use earth’s evolutionary history as evidence for the frequency of intelligent life? Naively, one answers such questions first, then decides what to do about it. And I’m inclined to take the naive project on its face.

I think Carlsmith is here trying to defend the project of having beliefs, which I think is a very good project indeed. Having a map-of-the-territory that’s neutral about strategy and works regardless of who you are is excellent, and worth pursuing. But where I think Carlsmith is going wrong is in saying that we should be able to entirely set aside consideration of betting, decision theory, and values when trying to reason about the world in the context of anthropics. Indeed, I think a huge part of my core thesis is that it’s vital to let strategic/value considerations absorb some of the intuitive answers conjured by anthropic thought experiments so that we can keep the realm of beliefs clean and simple. Even though they disagree on how to bet and what to anticipate, Based and Spread people should be able to agree on what to believe.

Moving on, the last thing I want to address is “splitting” and how to handle “the anthropic trilemma.” Here’s Paul Christiano:

Consider a computer which is 2 atoms thick running a simulation of you. Suppose this computer can be divided down the middle into two 1 atom thick computers which would both run the same simulation independently. We are faced with an unfortunate dichotomy: either the 2 atom thick simulation has the same [decision-theoretic] weight as two 1 atom thick simulations put together, or it doesn't.

Eliezer Yudkowsky:

So here's a simple algorithm for winning the lottery:

Buy a ticket. Suspend [the computer simulating your mind] just before the lottery drawing - which should of course be a quantum lottery, so that every ticket wins somewhere. Program your computational environment to, if you win, make a trillion copies of yourself, and wake them up for ten seconds, long enough to experience winning the lottery. Then suspend the programs, merge them again, and start the result. If you don't win the lottery, then just wake up automatically.

The odds of winning the lottery are ordinarily a billion to one. But now the branch in which you win has your "measure", your "amount of experience", temporarily multiplied by a trillion. So with the brief expenditure of a little extra computing power, you can subjectively win the lottery - be reasonably sure that when next you open your eyes, you will see a computer screen flashing "You won!" As for what happens ten seconds after that, you have no way of knowing how many processors you run on, so you shouldn't feel a thing.

More generally, how do we count people? Are multiple computers running the same mind through the same series of steps two different people? Is mind running on a thick computer “more people” than one running on a thin computer? I think the right answer is mu — the categories are made up according to what’s useful, which depends on our values.

Two simulations with the exact same mental state are worth twice as much in some ways, such as consuming twice as much power to run. And they’re worth exactly the same as one instance in other ways, such as diversity of memories. One way of counting people that I find meaningful is in terms of freedom and longevity. If I split into two copies that think the same thoughts and then get merged, I think that’s pretty similar to only having one self. But if each of those copies is released to freely interact with the world (and potentially diverge), then suddenly I want to see those as approximately twice as much self. More broadly, I think it’s worth recognizing that the Cartesian theater is an illusion, and the only sense in which there’s a countable being is in the particulars of how we choose to count.