Natalism (Part 2: Incentives)

TLDR: Paying parents to have kids works. Utopia further incentivizes parents by giving them impact certificates for their children’s lifetime achievements.

Prerequisites: Part 1

People are good. They create wealth and benefit society. So why are birth-rates going down? And how might we get them going back up?

The story about declining birth rates is a complicated one, involving factors such as declining religiosity, increasing urbanism, better health, more participation of women in the workforce, changing social priorities (i.e. “status”), increased pessimism about the future, and more. But one basic story that I think explains a lot (though clearly not all) is that what’s in the interest of society is not necessarily in the interest of the individual; children are really expensive in both money and time, and on purely economic grounds, usually a net-negative for the parents.

This is distinct from the question of whether it’s “too expensive” to have kids. People in the past used to be poorer and have more kids, and a cursory glance at the western world will reveal many people who could afford to have more kids if that was their priority. Rather, I want to highlight how people with kids are less wealthy than their peers, have less free time, and are less happy on average (at least on a moment-to-moment basis for the first decade of their child’s life).

This wasn’t true in the past! In the days when over 90% of people were farmers, people often relied on their children for economic support, and there often wasn’t a need to trade off between having a big family and being wealthy. Larger families often also meant increased opportunities from marriages and politics, back when communities were smaller and there was less travel. Perhaps most importantly, before nation-states took charge of social welfare, children were seen as vital caretakers in old-age.

There are many good reasons to be a parent beyond the economic incentives, of course. The joy of children is largely intrinsic, and even if they were wholly burdensome, I think Utopia would be full of children. But economic drivers and questions of incentives are an important chunk of understanding why the population growth rate is going down.

The Cost of Kids

Having kids is financially expensive. The medical care associated with pregnancy and birth alone can easily cost tens of thousands of dollars,1 and the overall cost of raising a child to adulthood totals in the hundreds of thousands of dollars,2 not to mention the more subtle financial drain from lost productivity due to childcare, pregnancy, illness, loss of sleep, and other side-effects of parenthood. Many parents also often see themselves as responsible for at least assisting their children with college or other early-adulthood expenses, which can make things even more expensive.

But it gets worse. The cost of raising a kid is heavily subsidized by society, primarily in the form of public schooling, but also though healthcare subsidies, grants to higher education, and social programs.3 While government expenditure varies significantly from place to place, it’s roughly on the order of $10k-$20k/year per child in wealthy countries like the USA, adding up to perhaps an amount comparable to what’s paid by parents.

If we combine the immediate financial costs paid by parents and governments, as well as the opportunity costs and other social costs of raising a child, I think a good estimate is that each child costs about a million dollars to raise to normal standards in a western household. For reference, the GDP/capita in the USA is ~$75k/year, and only about half of the population is employed, so a million dollars is close to the total economic output of the average worker for seven years.4

Rewarding Parents

From this math we can see how great kids are from the economic perspective of society. If the average child ends up working for 21 years,5 they’re producing three times as much value as they cost to create. The costs/benefits are remarkably similar from the perspective of a government budget, since governments pay about 1/4 of the costs and acquire about 1/4 of a worker’s production in taxes. But even if the government paid 100% of the financial costs (or 150%!), and simply left the time/opportunity costs to be paid by the parents, it would still be an overall win from the perspective of that nation’s budget (at least in the long-term).

We can imagine a country like the USA offering to give parents $30k/year per child (tax free! on top of other benefits!) as an incentive to encourage more babies, and in the long-run this would likely be budget-positive. Of course, it might bring in more revenue to offer less, since people are intrinsically motivated to have kids. Much like a Laffer curve, the best balance is probably somewhere in the middle, regardless of whether one is thinking from the perspective of overall social prosperity or simply about the state budget.6 Still, there’s a strong case to be made for offering even more financial assistance to parents, beyond what is already provided through public education and the like. If parents are naturally motivated to see two of their children grow up, governments could offer large cash incentives for the third child and onwards.

And several countries do this! … To some degree.

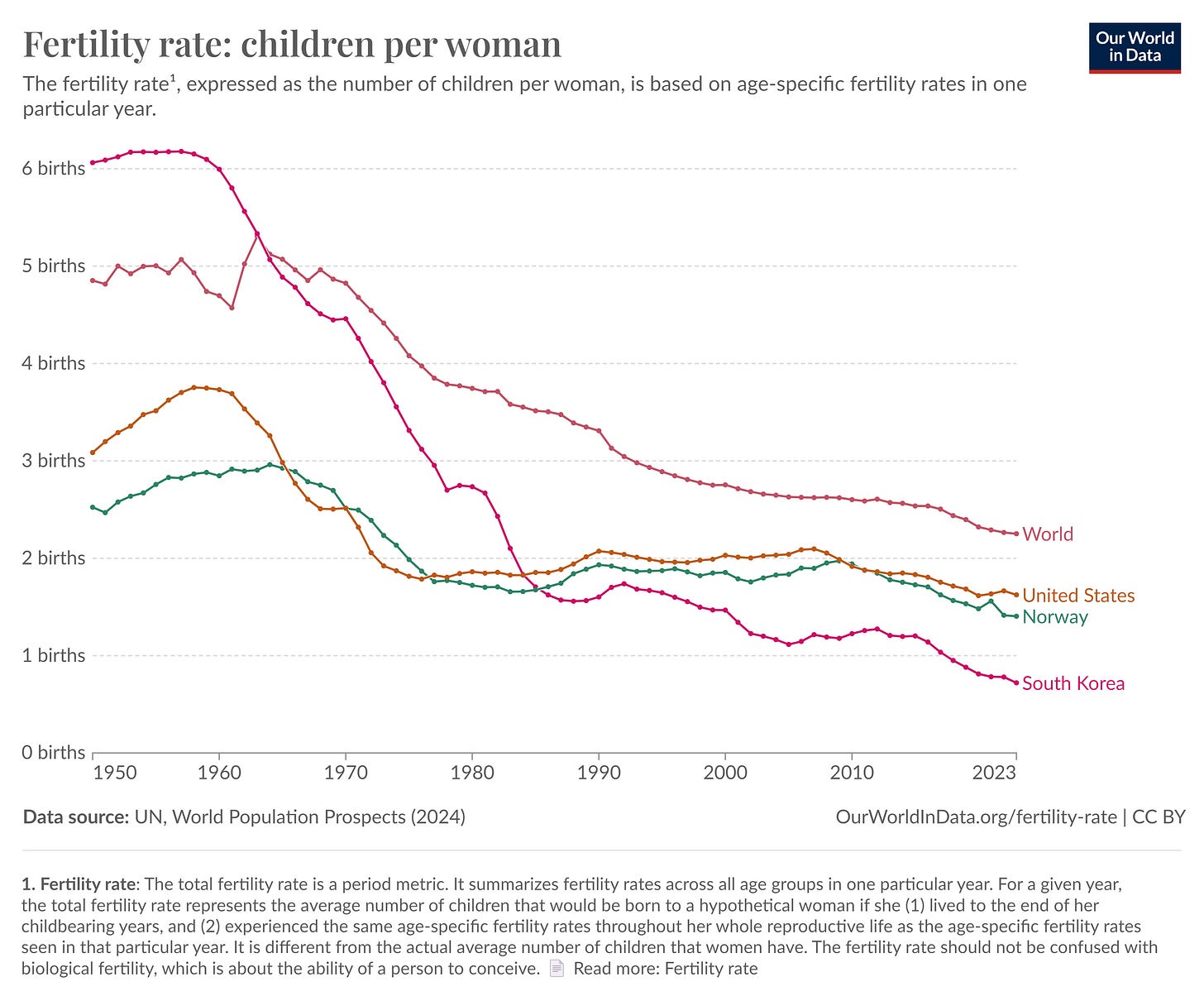

First, there are direct tax credits, which are conceptually very similar to a direct monetary transfer. The child tax credit in the USA is about $2k/year,7 for instance. Norway has an even more generous program for encouraging children; in addition to a similar-size tax credit, substantial parental leave, and free schooling, parents can expect to receive direct cash payments of about $2k/year per child (with single parents getting somewhat more). But despite all this, the Norwegian fertility rate continues to be well below replacement levels, and is comparable to countries with weaker incentives, such as the USA.

South Korea, the country with the lowest fertility rate in the world (0.7 children per woman), also offers significant financial incentives to parents. Families with a child born in 2024 can expect over $2,750/year in financial assistance8 until the child is at least eight years old. And while the exact amount depends on income, Korea also offers a comparably large incentive through reduced income taxes.

It’s tempting, on the surface, to look at cases like Korea and Norway and conclude that these kinds of programs don’t work. After all, their birth rates are still crashing. But notice that countries with precipitating fertility rates are exactly the places we’d expect to experiment with rewarding parents, so our only real conclusion should be that these payments are insufficient to reverse the prior trend. Indeed, when economists examine the data closely, the typical finding is that these kinds of programs do have an impact! The fertility crisis in these places would likely be even worse in the absence of financial assistance. Many of these incentives are new, especially in South Korea, and the culture around family-planning tends to take years to adapt. The fertility rate in Korea is expected to start climbing again in 2026.

It’s also worth noting that for the most part, even the most generous governmental support is still very, very low compared to the costs of raising a child. We’re nowhere near the extreme levels I proposed earlier. It seems reasonable to me that if you try giving a little money and it works a little bit, but you need it to work a lot, perhaps you should try giving a lot of money.

Natalist Culture

I’m a big fan of direct cash transfers as a way to set up incentives, but even I will admit that sometimes the best way to move the needle is through culture and status. The decision to try and have a large family ultimate derives from a sense of desire in the minds of the prospective parents, and that desire is often deeply linked to stories about what’s important in life and how to get it. In cultures where having large families is high-status, such as orthodox Israelis, more couples seek to have many kids.

There are many top-down things that a society can do to promote certain cultural norms. An easy victory is to push for more official holidays where people are discouraged from working, and instead to spend time with their families. If possible, including family and fertility related themes seems good, rather than simply taking time off to go to the beach. Throw a festival in the town square where all the kids are invited to come and play games. Set up a Schelling-point event where young couples are encouraged to propose and/or celebrate their engagements together with fireworks and music and stuff. Things like that.

Society can also fund media that promotes natalism or institutions that assist with building families, such as adoption centers, daycares, fertility clinics, and dating apps. While the separation of church and state is important, natalist religions should at least not be oppressed, and organizations within such religions might also be worth sponsoring on purely secular grounds. Regardless, the most efficient way to distribute funding to organizations and artists is probably using large, predictable prizes.

And of course, there’s much that can be done by individuals on the level of communities and individual relationships. Make being a parent cool, even if you aren’t one. Remind yourself that you were a terrible child once upon a time whenever you encounter an obnoxious child in a restaurant or airplane. Offer discounts to parents as a form of price-discrimination. Don’t insist that parents invest all their time and attention into their kids, especially if they have just one or two—it’s fine to lean heavily on external childcare. Just as the YIMBY movement is doing wonders for housing, a movement of enthusiastic natalists could be quite compelling.

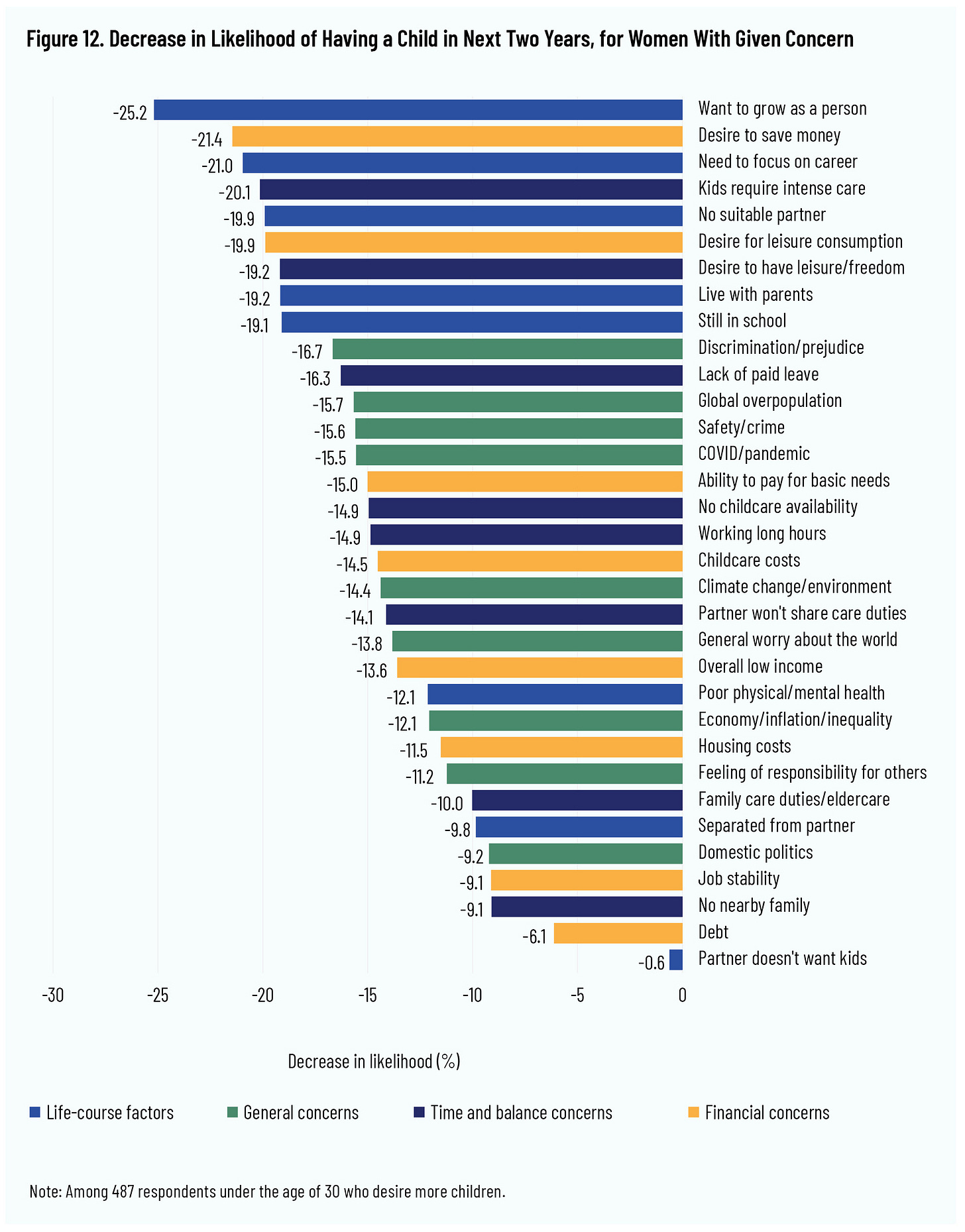

The disconnect between the desires of individuals and the prosperity of society is tragic in itself, but things are, sadly, even worse, especially in urban areas with lots of women participating in the workforce. Many studies have shown that women in wealthy countries often have fewer children than they want. While we can’t fix all of the issues that create this gap, we can, and should, fix those we have power over.

Utopian Natalism

People in Utopia don’t fear overpopulation. Rather, they welcome the prospect of new people as a source of wealth and abundance, and encourage having large families as part of that. One of the most direct ways that being a parent is encouraged is through giving access to almost all of their children’s basic income. Many parents (including foster parents) in Utopia simply have large families and live in low cost-of-living areas of the world, entirely off the government’s dime. Rather than being seen as freeloaders, these parents are celebrated in media as helping raise a disproportionate chunk of the next generation. Many Utopians know multiple friends from such households, and many young professionals and students in Utopia aspire to find the right partner and settle down in a quiet town to raise a big family.

While families in Utopia are diverse, the distribution is weighted more towards the big-family end of the spectrum than our world. Many families have no kids, but many have more than four. The main reason for this is that there are gains to be made in specializing in being a parent: siblings can share rooms, get hand-me-downs, and take advantage of established patterns of activity. The primary reason not to have a large family is that it’s too expensive, but this is less true in Utopia thanks to the way basic income naturally scales with the number of people in the house. Most importantly, perhaps, Utopia’s high land-value taxes make living space in urban areas very expensive, and so there’s a lot of pressure for parents, even of only two kids, to move out of high-productivity areas to quiet, rural parts of the world where there are fewer jobs, but cheaper cost of living. And at the point where you’ve made that kind of commitment to having a family, it often makes sense to go further.

Beyond basic income, most of the institutional natalism in Utopia is a product of private philanthropy and some local governments. And in this, prizes play a particularly large role. Not only are there prizes provided to the best stories promoting parenthood and big families, and prizes for sources of information to potential parents, but there are also prizes given to parents themselves.

In Utopia, when a baby is registered as a person and starts collecting basic income, the government awards the parents with impact certificates for the wholistic lifetime achievements of their child. Many parents give some share of those certificates to that child, others in the family, or to friends in exchange for becoming something like a godparent. Other parents sell their certificates as an immediate financial reward for having a kid. Some schools or tutors ask to be paid in impact shares for the child they’re taking on as a student. Regardless of who has the shares down-the-line, at some point that child might grow up and accomplish something great. Perhaps they become a great musician, or scientist, or explorer. Regardless of how they excel, the prize money is paid out to the holders of those impact certificate shares (often the parents themselves) in recognition for having invested in someone special.

Because lifetime achievement prizes are glamorous, and more likely to be claimed by elites, impact certificates are a way that Utopia incentivizes large families among the wealthy. Being the holder of an impact certificate for a hero of civilization is a great honor, and ultra-wealthy families with dozens of children (sometimes through surrogate mothers) are rightly celebrated in Utopia as hotbeds of next-generation leadership and excellence. Some prizes are even exclusive to those with several older siblings, providing a unique honor to large families.

Thanks to carefully tracking negative externalities, such as pollution and congestion, Utopia is sustainable, even as it grows. Utopians eat much, much less meat, allowing for more people to be fed from the same amount of land. Generally better policies in Utopia lead to more efficiency, and thus more overall prosperity, which in turn supports a larger population. Where the exponential population growth rate in our world slowed down in the 70’s, we can imagine Utopia continuing to grow, such that in a comparable 2024 the population of Utopia is over 10.5 billion.

In Utopia, when the population seems to be growing too quickly, the futarchy can restrict a variable called “BRCG,” and thereby reduce the basic income for families that (then) decide to have a lot of kids. Likewise, when the population growth slows, BRCG can be set higher, encouraging a return to the exponential baseline.

Utopia’s broadly positive outlook towards a future of progress and expansion gives a reason for people there to be optimistic and expect their children to have better lives than their parents. Utopians look up to the stars at night and dream of an even bigger, more populous universe.

Health insurance usually pays for most costs associated with pregnancy and birth.

The overall costs vary widely depending on socioeconomic status and where one lives. This estimate from 2023 suggests that it ranges from an average of about $15k/yr in cheap parts of the USA to $33k/yr in expensive urban centers. This 2018 study suggests that parents in the top-90th percentile by income spend more than six times as much on their children than those in the bottom quartile.

Tax credits aren’t a cost of children, per se, but merely a redistribution of the tax burden away from parents.

Those wondering why the average salary isn’t even close to $150k/year, it’s because:

Around a third of the gains from a worker goes to their employer. (The specific split depends on factors like how much bargaining power the worker has.)

We need to factor in employee benefits, such as healthcare and pensions.

We’re calculating the mean production rather than the median, and there are always massive outliers when it comes to anything involving money.

This is probably an underestimate, but remember that many people don’t become “workers” for one reason or another (e.g. disability, death, or being a caregiver such as staying home to raise kids). (And to be clear: staying home to raise kids is valuable! The point about “average worker” is merely an intuition pump approximation to avoid an alternate approximation wherein people produce ~$75k in value each year regardless of whether they’re working. The story of marginal people producing, on average, several times what was invested in raising them from childhood works regardless of how we carve things up.)

Of course, an even bigger win would be to somehow have new people show up in one’s country at prime working age, thus skipping any need to pay the up-front investment of raising them as a child, but still being able to benefit from their productive output.

The CTC is $2k/year at the time of writing, but was only $1k/year prior to 2017, and is currently scheduled to go back to that level in 2025.

The payments are uneven, with a single grant occurring at birth, and the specific quantity varying year-to-year.