Natalism (Part 1: Basics)

TLDR: Since the onset of the industrial revolution, each additional person more than pays for their consumption of resources, and thus the overall effect of having more children is positive, and good for society.

Prerequisites: In theory none, but it’ll help to know about Congestion Pricing, Georgism, and Energy.

Are there too many people, or not enough?

First, we should recognize that this is a somewhat silly question. Some places in the world very likely have too many people in them, while others are in desperate need of more people. Likewise, are we considering worlds where a different number of people come with correspondingly more/less wealth, or are we simply imagining adding/subtracting people all at once and dealing with the resulting economic shockwaves?

But secondly… more people would clearly be good. It’s not even close.

Malthusian Fears

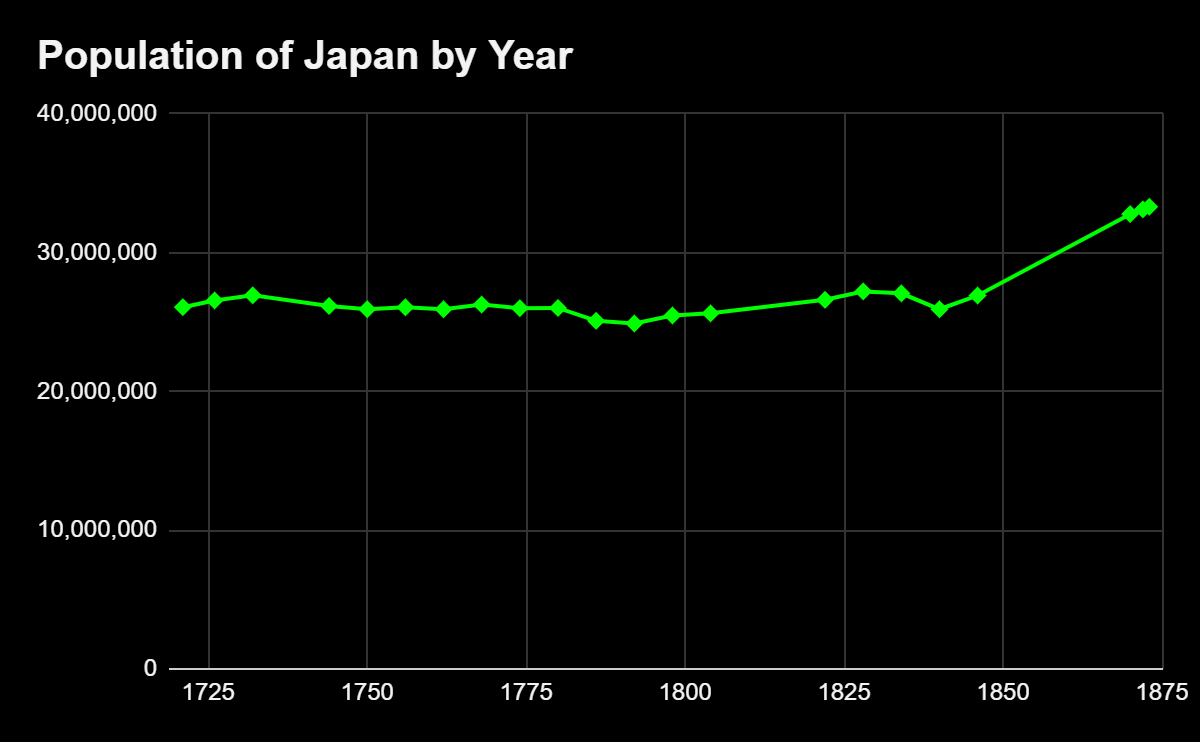

People have been worried about overpopulation for a long time, and reasonably so! When Thomas Malthus published An Essay on the Principle of Population in 1798, the industrial revolution was only in its early infancy and lots of people were starving. For basically all of human history, chronic starvation (i.e. not from a random shock like a war or drought or price-controls) was a sign of overpopulation, and the carrying capacity of a country was relatively fixed. At a given level of sophistication (technological, social, capital), the land in an area can only support so many mouths, and one should expect running up against resource limitations to be the norm.

But Malthus was wrong. England (and the world) wasn’t overpopulated in 1800, and in fact grew significantly over the next centuries, from a population of less than 10 million people, to over 50 million, while simultaneously making food cheaper and more abundant than ever. The secret, of course, was industry. Or more specifically, it was the exponential rise in the efficiency and availability of resources thanks to invention and economies of scale.

Benefitting from Scale

Information is pretty magical compared to physical goods. As the saying goes, if you have a chair and I take your chair, you stop having a chair, but if you have a brilliant idea and I “take” your idea, now we both have that brilliant idea. The only scarcity in the realm of information is that which we artificially impose so as to solve the public-goods-funding-problem, and the basic fact that transmitting knowledge requires paper, ink, transistors, electricity, quiet time to study, et cetera.

This means that intellectual work scales extremely well with population size. To see this in extremis, consider a society consisting of a single person, named Adam. Adam may be able to hunt/gather/garden well enough to live, and he might even be brilliant enough to develop an innovation or two in providing for himself, but as busy as he is surviving, he’ll never have enough time to learn how to build a complex chemical processing facility. On the other hand, we can imagine a society composed of an infinite number of planets connected by magical telepathy that allows fast communication between them. Even when starting at a comparable level of technological sophistication, the infinite planets will find approximately all of the innovations right away and they’ll spread like wildfire, quickly advancing technology that improves standards of living and unlocks new innovations.

In this way, we can see communication and transportation technologies1 as increasing the effective population of the world, at least from the perspective of sharing innovation. Before the formation of the Silk Routes, we can imagine Europe and Asia almost like two distinct worlds, each limited in size. Once connected, Europe was not only able to benefit from access to physical goods like spices and silks from the East, but also inventions such as paper, gunpowder, the number zero, porcelain, and many others. Likewise, connection with the West benefitted those in Asia by introducing innovations in glassblowing, oil painting, astronomy, cartography, and more.

Intellectual work is an extreme case of benefitting from scale, but in fact, almost all areas of work benefit from a large population. The basic story is that trade between specialists is almost always a more efficient way to set things up than local-production by generalists. Some of this comes down to not needing to know as many things in order to be productive—I don’t need to know how to grow/harvest/prepare coffee beans in order to be good at making a pot of coffee. But some of it is as basic as investment in specialized machinery—building a factory that makes ball-bearings is overkill if you’re the only customer, but makes total sense in a massive economy.

The Resource Race

Thus we find that there’s a natural sub-question that we’d like to answer as part of investigating whether it would be good to have more people around: does adding more people lead to more scarcity due to having more mouths to feed off a fixed amount of land, or does it lead to more abundance due to non-rivalrous goods and economics of scale? Prior to the industrial revolution, it seems like the answer was often “scarcity” but in this modern era I believe the answer is “abundance.” It’s not obvious from first-principles, however, so let’s look at the data.

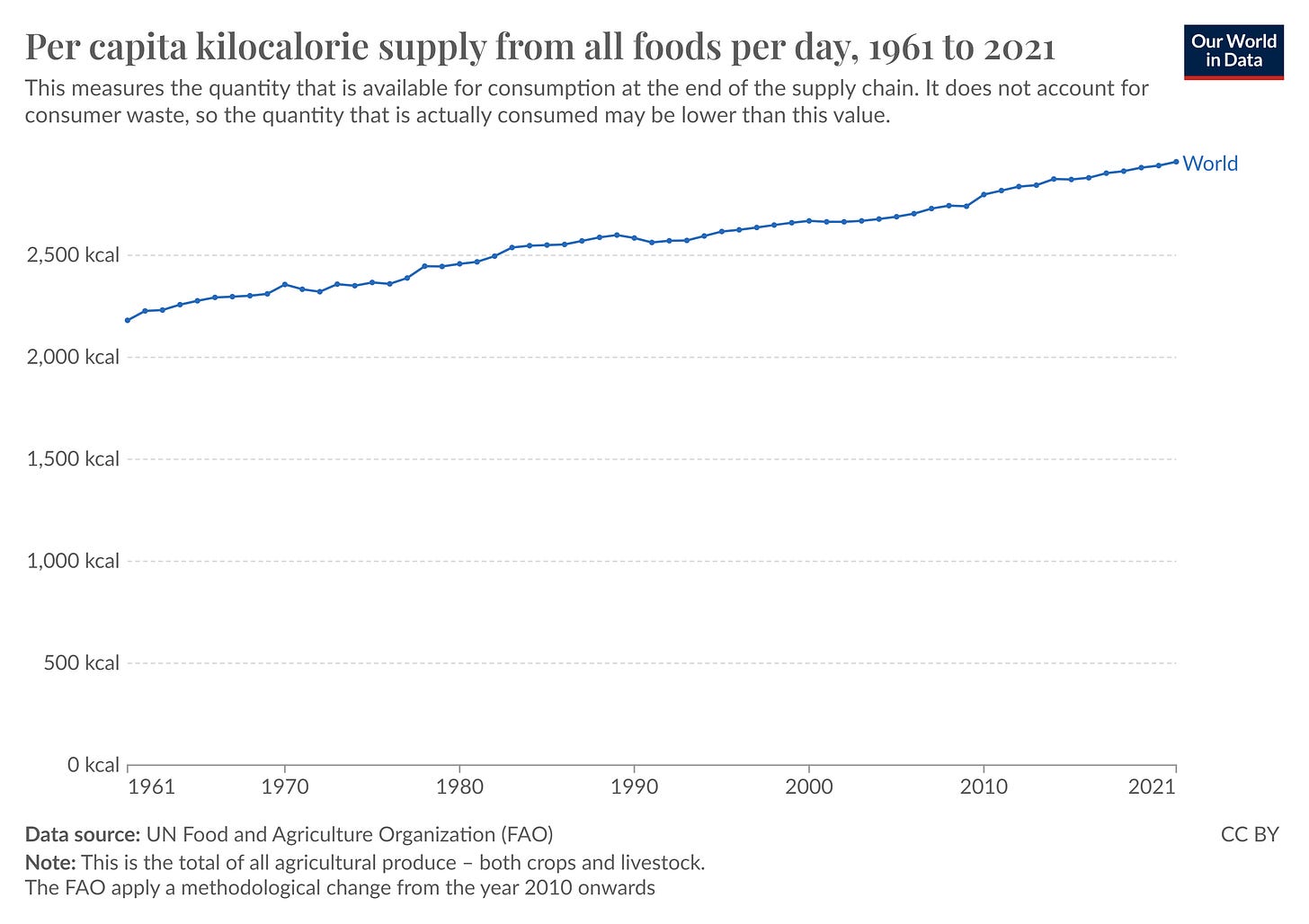

The above graph shows that even as the world population grew from ~3B people to ~8B, the food production per capita not only kept pace, but significantly increased. And we should expect that this understates the improvement, since people only want to eat a limited amount of food each day, and we can speculate that at a certain point these calories are mostly being wasted and/or contributing to obesity instead of reflecting meaningful abundance.

Perhaps we should be looking at some other resource. We can grow more food, but we can’t grow metal. With an exponentially growing population, we might naively predict the demand, and thus the price of metal to increase. Well, as it turns out, economics professor Julian Simon and Paul Ehrlich, neo-Malthusian author of The Population Bomb, quite virtuously made a bet on exactly this topic in 1980. Simon was so confident in abundance that he gave Ehrlich the freedom to choose any commodities and any time frame. Ehrlich then chose five metals and a timeframe of one decade. All five metals, and almost all other commodities, continued to grow cheaper as time went on. Ehrlich’s apocalyptic prophesy was just as wrong as Malthus’.2

Indeed, I believe that one of the best (though still imperfect) measures of the effect of marginal people is this graph:

Even as the population has been growing exponentially, the GDP per capita has also been growing exponentially! It’s an exponential on top of an exponential! The compounding effects of having lots of people driving progress which allows for more people which drives more progress is perhaps the greatest success story in all of human existence. On its face it’s extremely foolish to want to stop that virtuous cycle. Our world is a nice place to live in large part because the population is so high.

Inequality and the Demographic Transition

This story of success and growth is not without its drawbacks, so let’s address them directly. First, it’s important to notice that despite having vastly more total resources than ever before, it’s likely the case that more people are going hungry compared to ten years ago. Progress is at least slowing down in many places, and there are many people, even in rich, abundant countries that struggle to meet their basic needs. Nothing in our story of abundance guarantees that resources will be evenly or fairly distributed, and a strong case can be made that more effort needs to be put in to ensure that even as new techniques for efficiently extracting fuel and minerals from the earth are found, that the capture of those resources benefits everyone, rather than the select few who were already well-positioned to extract them.

There are many things that can be done to decrease inequality (such as Georgist land reform and basic income), which have little to do with the size of the population per se. And we should note that in isolation, everyone having more/fewer kids doesn’t really impact inequality. But we must also acknowledge that choices don’t exist in isolation, and the decision to have more children is connected to the story of personal wealth.

One common perspective on the topic of overpopulation is: “it would be pretty bad if the species kept growing exponentially, but thankfully we don’t need to worry about that, because it turns out that humans naturally don’t want to have that many kids if they grow up in a country with low infant mortality and lots of education and opportunities for girls.” Many people have this perspective, but I’ll pick on Bill Gates as a particularly notable example.

I disagree with Gates about whether it would be good for the world to have many more people. But I agree that saving children’s lives and educating girls is good, and that a natural side-effect of this is decreased fertility, especially in the world’s poorest places. This change also helps reduce inequality, since more effort is spent accumulating wealth and working, compared to raising a large family. I don’t think we should make it a priority to try and get poor people to focus on family size, rather than moving up the economic-ladder, but I do think it’s important to note that those smaller families typically provide less overall benefit to society.

Part of noting this downside is celebrating, rather than shaming, poor folks who decide to have large families. But another part of it is noticing that natalism can have a directly positive effect on economic equality as well as overall prosperity if the wealthy have a disproportionate number of children.3

If two parents, each with 100M dollars, have a single child together and then die, (in the absence of taxes) that child will then have $200M. If this story is typical, and there’s no social mobility, the elite class will shrink and become wealthier at the same time, making society more unequal. But if those same parents had ten children, each child would only have a fifth of the wealth of their parents, alleviating the social tension (and, perhaps, the injustice) from having such a large wealth gap.

Crowdedness and Pollution

Another obvious downside to having a more populous world is that some places become more crowded. Where previously it might’ve been possible to gaze on the Grand Canyon without another human being in sight, or meet personally with the most famous person alive, things are vastly more crowded and competitive now. Finding parking in a metropolis is harder and more expensive than out in the country, and simply getting peace and quiet can become a luxury.

Space is, in other words, an inelastic resource. Even as demand increases, we struggle to find more of it, and the price thereby rises. It’s still possible to allocate that space efficiently, but this is a genuine tradeoff. Some people might prefer to live in a poor, empty world than a rich, crowded one. On the whole, however, I suspect most people prefer to have many goods and services (and to exist!), even if things get crowded occasionally.

A perhaps more serious inelastic resource is the the natural world’s absorption of pollution. In a world with a few thousand cattle farting, there’s basically no issue, as the methane in those farts breaks down over time and has little impact on the overall atmosphere. But scale that up to billions of cattle, and suddenly that methane becomes a major driver for global warming.

The good news for climate change and other environmental concerns connected to population, is that even though the ability for the natural environment to handle pollutants is inelastic, we don’t really care about that. What we care about is damage to the environment and to ourselves, and that is definitely able to be reduced through deliberate effort. It wouldn’t matter, for example, how much CO₂ we emit if we also used carbon-capture technologies to remove an equal amount from the air. Where nature fails, humanity can take up the slack.

Many technologies exist which can provide for our needs while also protecting the natural world, and with the proper incentives, we can protect the environment even as we grow, paying for the costs using the wealth generated by each generation. As a quick sanity check, we can imagine a world where we need to capture 35 billion tons of CO₂ annually (thus not assuming green sources replace fossil fuels). At an estimate of $200 per ton of captured carbon (thus not assuming carbon capture technology becoming more efficient with scale and technological progress), that’s a total cost of about 7 trillion dollars—only a fraction of the GDP of America, China, or Europe (much less everyone working together). It’s expensive to live sustainably, but not so expensive that marginal-people are a net-negative.

But How Many?

So if, at eight billion humans, each additional person creates more abundance than scarcity, at what population level should we expect this to change? Surely there’s a limit. How many people should we be aiming for?

Unfortunately, nobody knows. The ability for the population to keep growing and yet become more and more rich is largely a product of scientific breakthroughs. People in 1850 couldn’t have predicted the Haber–Bosch process and might’ve naively assumed that the limiting factor for ammonia production was the harvesting of guano from deserted islands. Those in 1925 couldn’t have predicted the work of Norman Borlaug and the specifics of the green revolution, and might’ve suspected that the world would soon run out of food. Trend lines can only give so much information.

We can’t predict the exact discoveries of the future, but we can notice that there seems to be no end in sight. Science and technological growth are continuing to surge forward, and we can only speculate where the eventual limit is.

Some day all the relevant inventions and discoveries will be known. Billions of years in the future, if there are still people, they almost certainly won’t be going through the particularly dramatic period of discovery that we are currently in. But a lot can happen between now and then. At the very least, we can notice that a large majority of the planet is covered in relatively unproductive water, and it seems plausible that, someday, a floating-farm might exist. (To say nothing of colonies in space or uploading into virtual reality.)

Regardless, on the margin right now, growth is good. More people are not just valuable as an ends in themselves, but also as an additional, helpful teammate in the great collaborative endeavor that we call civilization.

Sharing a common language and having rich interconnection also boosts effective population size for the same reasons.

Actually, Ehrlich was arguably even more wrong than Malthus. For instance, in The Population Bomb he infamously wrote: “If I were a gambler, I would take even money that England will not exist in the year 2000.”

It should be noted that the reverse is also true. If the poor are disproportionately having larger families, this makes inequality worse. The effect is lopsided, however, as poor people experience less intergenerational wealth transfer. Regardless, it seems foolish to blame poor people who decide to have large families for “exacerbating inequality” since, if inequality hurts anyone, it’s concentrated on exactly those who make that choice.